Eukaryote

An eukaryote is an organism with complex cells, or a single cell with complex structures. In these cells the genetic material is organized into chromosomes in the cell nucleus.

| Eukaryota | |

|---|---|

| |

| Eukaryotes and some examples of their diversity – clockwise from top left: Red mason bee, Boletus edulis, Common chimpanzee, Isotricha intestinalis, Persian buttercup, and Volvox carteri | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota (Chatton, 1925) Whittaker & Margulis, 1978 |

| Supergroups[2] and kingdoms | |

Eukaryotic organisms that cannot be classified under the kingdoms Plantae, Animalia or Fungi are sometimes grouped in the kingdom Protista. | |

Animals, plants, algae and fungi are all eukaryotes. There are also eukaryotes amongst single-celled protists. In contrast, simpler organisms, such as bacteria and archaea, do not have nuclei and other complex cell structures. Such organisms are called prokaryotes.

The eukaryotes are often treated as a superkingdom, or domain.

Eukaryotes evolved in the Proterozoic eon. The oldest known probable eukaryote is Grypania, a coiled, unbranched filament up to 30 mm long.[3] The oldest Grypania fossils come from an iron mine near Negaunee, Michigan. The fossils were originally dated as 2100 million years ago,[4] but later research showed the date as about 1874 million years ago.[5] Grypania lasted into the Mesoproterozoic era.

Another ancient group is the acritarchs, believed to be the cysts or reproductive stages of algal plankton. They are found 1400 million years ago, in the Mesoproterozoic era.[6]p57

The classification of the Eukaryota is under active discussion, and several taxonomies have been proposed. Modern versions disagree about the number of kingdoms.[7] It carrys DNA as well as it is an organism.

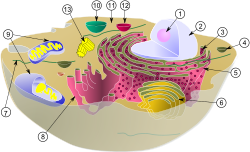

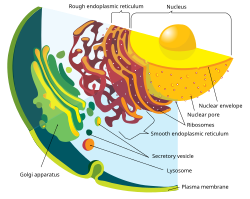

Structure

Eukaryotic cells are usually much bigger than prokaryotes. They can be up to 10 times bigger. Eukaryote cells have many different internal membranes and structures, called organelles. They also have a cytoskeleton. The cytoskeleton is made up of microtubules and microfilaments. Those parts are very important in the cell's shape. Eukaryotic DNA is put in bundles called chromosomes, which are separated by a microtubular spindle during cell division. Most eukaryotes have some sort of sexual reproduction through fertilisation, which prokaryotes do not use.

Prokaryotes do not have sexes, but they can pass DNA to other bacteria. Their cell division is asexual. Bacterial conjugation is when bacteria move a genetic element (often a plasmid or transposon) from one to another.[8][9]

Eukaryotes have sets of linear chromosomes located in the nucleus and the number of chromosomes is usually typical for each species.

Internal membrane

In eukaryotic cells, there are many things with membranes around them. All of them together are called the endomembrane system. Simple bags, called vesicles or vacuoles, are sometimes made by budding off other membranes, just like how children make bubbles with their toys. Many cells take in food and other things using something called endocytosis. In endocytosis, the membrane closest to the outside bends inwards and then pinches off to make a vesicle. Many other organelles that have membranes probably started off as vesicles.

The nucleus is surrounded by two membranes membrane that has holes in it so things can go in and out. The nuclear envelope has things sticking out of it that look like tubes and sheets. These are called the endoplasmic reticulum which is often shortened to ER. The ER is works with moving proteins around and allowing them to mature.

The ER has two parts, the rough ER and the smooth ER. The rough ER has ribosomes attached to it. The proteins made by the ribosomes attached to the rough ER go to the inside the rough ER, called the lumen. After that, they usually go into vesicles, which grow and pinch off from the smooth ER. In most eukaryotes, the vesicles with proteins inside fuse with piles of flattened vesicles called the Golgi bodies, where the proteins inside are changed again.

Vesicles are sometimes changed so they can do one thing very well. This is called specialization, or differentiation. For example, lysosomes have enzymes inside them that break down the food the comes from food vacuoles, and peroxisomes have enzymes that break down peroxide, a poison, so it is not poisonous anymore.

Many protozoa have contractile vacuoles, which are vacuoles that can fuse or pinch off from the outer membrane. Contractile vesicles are often used to get and get rid of unneeded water. Extrusomes shoot out stuff that make predators go away or catch food. In multicellular organisms, hormones are often made in vesicles. In the complicated plants, most of the inside of a plant cell is taken up by a central vacuole. That central vacuole is the main thing that keeps osmotic pressure so the cell can hold its shape.

Origin

Because the cell organelles of eukaryotes have different (polyphyletic) origins, the question arises as to whether the group is a unified clade or not.[10] It is certain that the protists are not.[11][12] Cell organelles are specialised units which carry out well-defined functions, like mitochondria and plastids. It is fairly clear now that all or most of these organelles have their origin in once-independent prokaryotes (bacteria or archaea), and that the eukaryote cell is a 'community of micro-organisms' working together in 'a marriage of convenience'.[13] The first such events took place between ancient bacteria to produce the double-membrane class known as gram-negative bacteria.[14] Since the gram-negative bacteria include the cyanobacteria, this was the first of several such events in the history of the eukaryotes.

Role of the Archaea

Recent research shows that "the known repertoire of ‘eukaryote-specific’ proteins in Archaea [indicate] that the archaeal host cell already contained many key components that govern eukaryotic cellular complexity".[15]

Taxonomy

Protista is a group of different single-celled organisms. More accurate taxonomies have been proposed, but scientists are still discussing them. For this reason, Protista is still useful for talking about these organisms. One modern scheme for the classification of the Eukarya is as follows:[16][17]

| Opisthokonts | Animals, fungi, choanoflagellates, etc. |

| Amoebozoa | Most lobose amoeboids and slime moulds |

| Rhizaria | Foraminifera, Radiolaria, and various other amoeboid protozoa |

| Excavates | Various flagellate protozoa |

| Archaeplastida (or Primoplantae) | Land plants, green algae, red algae, and glaucophytes |

| Chromalveolates | Heterokonts, Haptophytes, Cryptomonads, and Alveolates. |

However, in 2005, doubts were expressed as to whether some of these supergroups were monophyletic, particularly the Chromalveolata,[18] and a review in 2006 noted the lack of evidence for several of the supposed six supergroups.[19]

The Eukarya may only be unified in the sense that the cells are a community derived from bacteria and archaea; opinions vary. Like the Protista, the Eukarya may be a polyphyletic assembly, though a useful one. However, as mentioned above, all branches of the Eukarya have sexual reproduction.[20] That, and the general organisation of the nucleus, are the defining features. These two points are the main evidence for monophyletic origin.[21]

Related pages

References

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Identifiers at line 630: attempt to index field 'known_free_doi_registrants_t' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Identifiers at line 630: attempt to index field 'known_free_doi_registrants_t' (a nil value).

- ↑ Knoll, Andrew H. et al 2006. Eukaryotic organisms in Proterozoic oceans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 361 (1470): 1023–38. [1]

- ↑ Han T.M. & Runnegar B. 1992. Megascopic eukaryotic algae from the 2.1-billion-year-old negaunee iron-formation, Michigan. Science 257 (5067): 232–235. [2]

- ↑ Schneider D.A. et al 2006. Age constraints for Paleoproterozoic glaciation in the Lake Superior Region: detrital zircon and hydrothermal xenotime ages for the Chocolay Group, Marquette Range Supergroup. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 43, 571-591. [3]

- ↑ Clarkson E.N.K. 1998. Invertebrate palaeontology and evolution. Blackwell, Oxford.

- ↑ Luketa, Stefan (2012). "New views on the megaclassification of life". Protistology. 7 (4): 218–237. ISSN 1680-0826.

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 60–4. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ↑ Holmes R.K. & Jobling M.G.; et al. (1996). Genetics: conjugation. In: Baron's medical microbiology (Baron S. (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ Dyer B.D. and Obar R.A. 1994. Tracing the history of eukaryotic cells. Columbia N.Y.

- ↑ Margulis L & Dolan M.F. 2002. Early life: evolution on the Precambrian Earth. 2nd ed, Jones & Bartlett, Boston. p89

- ↑ Margulis L. Schwartz K.V. & Dolan M. 1999. Diversity of life: the illustrated guide to the five kingdoms. Jones & Bartlett, Boston, p94. In this work the authors propose 19 phyla for the Protista, and call this 'Kingdom' the 'Protoctista', a term which is unfortunately almost unpronounceable.

- ↑ Margulis L. and McMenamin 1990. Marriage of convenience. The Sciences 30, 31-36.

- ↑ Lake, James A. 2009. Evidence for an early prokaryotic endosymbiosis. Nature 460: p967.

- ↑ Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka, Katarzyna et al 2017. Asgard archaea illuminate the origin of eukaryotic cellular complexity. Nature (journal). 541 (7637): 353–358. [4]

- ↑ Adl S.M. et al 2005. The new higher level classification of eukaryotes with emphasis on the taxonomy of protists. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 52 (5): 399–451. [5]

- ↑ Burki F.; et al. (2007). "Phylogenomics reshuffles the eukaryotic supergroups". PLOS ONE. 2 (8): e790. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..790B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000790. PMC 1949142. PMID 17726520.

- ↑ Harper J.T; Waanders E. & Keeling P.J. 2005. On the monophyly of chromalveolates using a six-protein phylogeny of eukaryotes. Int. J. System. Evol. Microbiol. 55, 487–496. [6]

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Identifiers at line 630: attempt to index field 'known_free_doi_registrants_t' (a nil value). [7]

- ↑ Secondarily lost in some lines.

- ↑ Woese, Carl R.; Kandler, Otto & Wheelis, Mark L. 1990. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. 87, 4576–9. [8] Archived 2008-06-27 at the Wayback Machine

| Wikispecies has information on: Eukaryota. |