Adaptive radiation

Adaptive radiation is rapid evolutionary radiation. It is an increase in the number and diversity of species in each lineage. It produces more new species, and those species live in a wider range of habitats.[1]

Some definitions phrase it in terms of a single clade: "Adaptive radiation is the rapid proliferation of new taxa from a single ancestral group".[2] However, in the most striking cases, such as occurred in the Triassic after the greatest extinction event in Earth history,[3] many lines underwent rapid radiation simultaneously. This must have something to do with the availability of ecological niches and relative little competition.

The Ediacaran biota were the result of an early metazoan radiation. The greatest radiation of all took place early in the Cambrian period, when most of our animal phyla evolved: see List of animal phyla.

With less competition, groups diversify to fill available habitats and niches.[1] This is an evolutionary process driven by natural selection.[4]

The term was introduced and discussed by George Gaylord Simpson, the palaeontologist who contributed to the modern evolutionary synthesis.[5][6] Others prefer not to use the term. Robert L Carroll prefers to use the term major evolutionary transitions, though it turns out that all or most of these could also be described as adaptive radiations.[7] Others use terms like macroevolution, or even megaevolution, as if the processes are different from those which occur below species level. It is part of evolutionary theory that all processes take place at the level of populations. All agree, though, that the speed of evolution does change, however it is measured.

Measurement of rates of change

Records of timing are bedevilled by gaps in the fossil record, often at those crucial early stages when numbers are low and geographical distribution is severely restricted.[8] "In reality, there are long periods within nearly every lineage for which the fossil record remains unknown".[7]p297[9][10] These gaps affect our knowledge of timing, and of changes in body shape and function.

Nevertheless, when several distinctly new lines appear within a short period, it seems reasonable to say that the rate of change has been surprisingly fast. An example would be the appearance of new reptilian groups in the Upper Triassic. Using the term 'reptile' broadly, the groups include dinosaurs, pterosaurs, Chelonia (turtles), crocodylomorphs (early Crocodilia), phytosaurs, and ichthyosaurs a bit earlier (Middle Triassic).

These radiations occurred after the great Permian–Triassic extinction event that ended the Palaeozoic era. The Triassic itself had several lesser (but still significant) extinctions.[11][12] Unfortunately, the Triassic has the poorest fossil record of the whole of the Mesozoic era.

Causes

Innovation

The evolution of a new feature may let a group diversify because it makes possible new ways of living. A most striking example is the cleidoic egg,[13] which developed in early amniotes, and permitted vertebrates to invade the land. The cleidoic egg must have been developed in the latest Devonian or early Carboniferous. Amphibians, who branched off before this event, still lay their eggs in water, and so are limited in the extent to which they can exploit land environments.

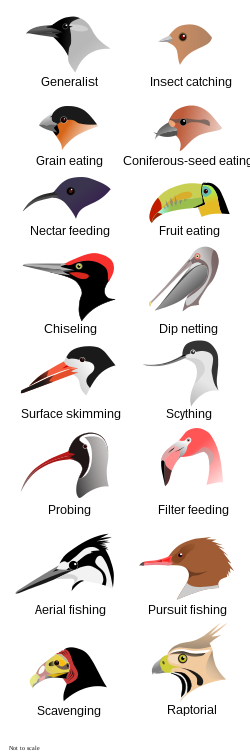

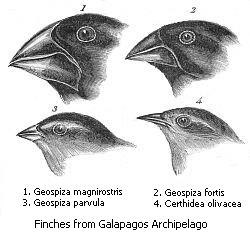

An example of a more modest innovation is the evolution of a fourth cusp in the mammalian tooth. This trait permits a vast increase in the range of foodstuffs which can be fed on. Evolution of this character has thus increased the number of ecological niches available to mammals. The trait arose a number of times in different groups during the Cenozoic, and in each instance was immediately followed by an adaptive radiation.[14] With birds, the evolution of flight opened new possibilities, and at least two huge adaptive radiations occurred (one before and one after the K/T extinction event).[15] Even more striking was the evolution of insect flight, which led to huge radiation in the Mesozoic era. Then, these insect groups developed ways of feeding on flowering plants. They now outnumber all other forms of animal life by quite a margin.[16]

Opportunity

Adaptive radiations often happen when organisms enter environments with unoccupied niches,[1] such as a newly formed lake or an isolated island chain. The colonizing population(s) may diversify rapidly and take advantage of all possible niches.[17] Opportunities occur when land bridges form between areas which were previously separate, and whenever species get to new place in the world.

In Lake Victoria, an isolated lake which formed recently in the African rift valley, over 300 species of cichlid fish radiated from one parent species in just 15,000 years.[18]

Vacant islands

In about 6,500 sq mi (17,000 km2), the Hawaiian Islands have the most diverse collection of drosophilid flies in the world, living from rainforests to mountain meadows. About 800 Hawaiian drosophilid species are known.

Studies show a clear "flow" of species from older to newer islands. There are also cases of colonization back to older islands, and skipping of islands, but these are much less frequent. By potassium/argon radioactive dating, the present islands date from 0.4 million years ago (mya) (Mauna Kea) to 10mya (Necker). The oldest member of the Hawaiian archipelago still above the sea is Kure Atoll, which can be dated to 30 mya. The archipelago itself, produced by the Pacific plate moving over a hot spot, has existed for far longer, at least into the Cretaceous. The Hawaiian islands plus former islands which are now beneath the sea make up the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain; and many of the underwater mountains are guyots.[19]

All of the native drosophilid species in Hawaiʻi have apparently descended from a single ancestral species that colonized the islands, about 20 million years ago. The subsequent adaptive radiation was spurred by a lack of competition and a wide variety of vacant niches. Although it would be possible for a single pregnant female to colonise an island, it is more likely to have been a group from the same species.[20][21][22][23]

There are other animals and plants on the Hawaiian archipelago which have undergone similar, if less spectacular, adaptive radiations.[24][25]

Mass extinctions

Adaptive radiations commonly follow mass extinctions. After an extinction event, many niches are left vacant. A classic example of this is the replacement of the non-avian dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous with mammals in the Palaeocene.

Great radiations

- The Cambrian explosion: the most famous of all adaptive radiations. Most phyla appeared during or just before the Cambrian.

- Flight: all forms of flying animals are highly successful

- Flight in insects: the Pterygota: the greatest number of living species are flying insects.

- Flight in birds: the origin of birds: the greatest number of land vertebrates.

- The Upper Triassic radiation of dinosaurs.

- The Upper Cretaceous radiation of flowering plants.

Adaptive Radiation Media

Related pages

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Schluter D. 2000. The ecology of adaptive radiation. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Stanley S.M. 1979. Macroevolution: pattern and process. Freeman, S.F. p65

- ↑ The P/Tr extinction event

- ↑ Mayer, Ernst. 2001. What evolution is. Basic Books, New York, NY.

- ↑ Simpson G.G. 1944. Tempo and mode in evolution. Columbia, N.Y.

- ↑ Simpson G.G. 1953. The major features of evolution. Columbia, N.Y.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Carroll, Robert L. 1997. Patterns and processes of vertebrate evolution. Cambridge.

- ↑ A group has to be a success before it can invade other areas.

- ↑ Benton M.J. 1993. The fossil record 2. Chapman & Hall, London.

- ↑ Raup D.M. 1995. The role of extinction in evolution. In Tempo and mode in evolution, eds Fitch & Ayala. Washington D.C. National Academy of Sciences.

- ↑ Sahney S. and Benton M.J. 2008. Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time. Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series B 275, 759-765.

- ↑ Benton M.J. 1990. The reign of the reptiles. Kingfisher, London.

- ↑ Eggs like those of modern reptiles and birds.

- ↑ Jernvall J. Hunter J.P. Fortelius M. 1996. Molar tooth diversity, disparity, and ecology in Cenozoic ungulate radiations. Science 274: 1489.

- ↑ Feduccia A. 1999. The origin and evolution of birds

- ↑ Grimaldi D. and Engel M.S. 2005. Evolution of the insects. Cambridge University Press. 11–15: How many species of insects? ISBN 0-521-82149-5

- ↑ Grant P.R. 1999. The ecology and evolution of Darwin's finches. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- ↑ Barlow G. 2002. The cichlid fishes: nature's grand experiment in evolution.

- ↑ Frankel, Henry R. 2012. The continental drift controversy: introduction of seafloor spreading, p. 292; Clague D.A. & G.B. Dalrymple. 1987. The Hawaiian-Emperor volcanic chain, Part I. Geologic evolution, In R.W. Decker, T.L. Wright & P.H. Stauffer, eds. Volcanism in Hawaii, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1350, pp. 5-54; retrieved 2012-6-9.

- ↑ Carson H.L. 1970. Chromosomal tracers of evolution. Science 168, 1414–1418.

- ↑ Carson H.L. 1983. Chromosomal sequences and interisland colonizations in Hawaiian Drosophila. Genetics 103, 465-482.

- ↑ Carson H.L. 1992. Inversions in Hawaiian Drosophila. In: Krimbas C.B. & Powell J.R. (eds) Drosophila inversion polymorphism. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 407-439.

- ↑ Kaneshiro K.Y. Gillespie R.G. and Carson H.L. 1995. Chromosomes and male genitalia of Hawaiian Drosophila: tools for interpreting phylogeny and geography. In Wagner W.L. & Funk E. (eds) Hawaiian biogeography: evolution on a hot spot archipelago, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C. 57-71

- ↑ Craddock E.M. 2000. Speciation processes in the adaptive radiation of Hawaiian plants and animals. Evolutionary Biology 31, 1-43.

- ↑ Ziegler A.C. 2002. Hawaiian natural history, ecology and evolution. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.