Quantum mechanics

| Quantum mechanics |

|---|

|

|

Fundamental concepts

|

|

Equations

|

|

Scientists

|

Quantum mechanics explains how the universe works with things that are even smaller than atoms. It is also called quantum physics or quantum theory. Mechanics is the part of physics that explains how things move and quantum is the Latin word for 'how much'. A quantum of energy is the least amount possible (or the least extra amount), and quantum mechanics describes how that energy moves.

Atoms were once believed to be the smallest pieces of matter, but modern science has shown that there are even smaller particles called subatomic particles, like protons, neutrons and electrons. Quantum mechanics describes how the particles that make up atoms work.

Quantum physics also tells us how electromagnetic waves (like light) work. Wave–particle duality means that particles behave like waves and waves behave like particles. (They are not two kinds of things, they are something like both: this is called duality.) Much of modern physics and chemistry can be described and understood using the mathematical rules of quantum mechanics.

The math used to study subatomic particles and electromagnetic waves is very complex because they act in very strange ways.

Waves and photons

Photons are particles that are point-sized, tinier than atoms. Photons are like "packets" or packages of energy. Light sources such as candles or lasers produce light in bits called photons.

The more photons a lamp produces, the brighter the light. Light is a form of energy that behaves like the waves in water or radio waves. The distance between the top of one wave and the top of the next wave is called a 'wavelength'. Each photon carries a certain amount, or 'quantum', of energy depending on its wavelength.

A light's color depends on its wavelength. The color violet (the bottom or innermost color of the rainbow) has a wavelength of about 400 nm ("nanometers") which is 0.00004 centimeters or 0.000016 inches. Photons with wavelengths of 10-400 nm are called ultraviolet (or UV) light. Such light cannot be seen by the human eye. On the other end of the visual spectrum, red light is about 700 nm. Infrared light is about 700 nm to 300,000 nm. Human eyes are not sensitive to infrared light either.

Wavelengths are not always so small. Radio waves have longer wavelengths. The wavelengths for an FM radio can be several meters in length (for example, stations transmitting on 99.5 FM are emitting radio energy with a wavelength of about 3 meters, which is about 10 feet). Each photon has a certain amount of energy related to its wavelength. The shorter the wavelength of a photon, the greater its energy. For example, an ultraviolet photon has more energy than an infrared photon.

Wavelength and frequency (the number of times the wave crests per second) are inversely proportional, which means a longer wavelength will have a lower frequency, and vice versa. If the color of the light is infrared (lower in frequency than red light), each photon can heat up what it hits. So, if a strong infrared lamp (a heat lamp) is pointed at a person, that person will feel warm, or even hot, because of the energy stored in the many photons. The surface of the infrared lamp may even get hot enough to burn someone who may touch it. Humans cannot see infrared light, but we can feel the radiation in the form of heat. For example, a person walking by a brick building that has been heated by the sun will feel heat from the building without having to touch it.

The mathematical equations of quantum mechanics are abstract, which means it is impossible to know the exact physical properties of a particle (like its position or momentum) for sure. Instead, a mathematical function called the wavefunction provides information about the probability with which a particle has a given property. For example, the wavefunction can tell you what the probability is that a particle can be found in a certain location, but it can't tell you where it is for sure. Because of this uncertainty and other factors, you cannot use classical mechanics (the physics that describe how large objects move) to predict the motion of quantum particles.

Ultraviolet light is higher in frequency than violet light, such that it is not even in the visible light range. Each photon in the ultraviolet range has a lot of energy, enough to hurt skin cells and cause a sunburn. In fact, most forms of sunburn are not caused by heat; they are caused by the high energy of the sun's UV rays damaging your skin cells. Even higher frequencies of light (or electromagnetic radiation) can penetrate deeper into the body and cause even more damage. X-rays have so much energy that they can go deep into the human body and kill cells. Humans cannot see or feel ultraviolet light or x-rays. They may only know they have been under such high frequency light when they get a radiation burn. Areas where it is important to kill germs often use ultraviolet lamps to destroy bacteria, fungi, etc. X-rays are sometimes used to kill cancer cells.

Quantum mechanics started when it was discovered that if a particle has a certain frequency, it must also have a certain amount of energy. Energy is proportional to frequency (E ∝ f). The higher the frequency, the more energy a photon has, and the more damage it can do. Quantum mechanics later grew to explain the internal structure of atoms. Quantum mechanics also explains the way that a photon can interfere with itself, and many other things never imagined in classical physics.

Quantization

Max Planck discovered the relationship between frequency and energy. Nobody before had ever guessed that frequency is directly proportional to energy (this means that as one of them doubles, the other does, too). Under what are called natural units, then the number representing the frequency of a photon would also represent its energy. The equation would then be:

- [math]\displaystyle{ E = f }[/math]

meaning energy equals frequency.

But the way physics grew, there was no natural connection between the units that were used to measure energy and the units commonly used to measure time (and therefore frequency). So the formula that Planck worked out to make the numbers all come out right was:

- [math]\displaystyle{ E = h \times f }[/math]

or, energy equals h times frequency. This h is a number called Planck's constant after its discoverer.

Quantum mechanics is based on the knowledge that a photon of a certain frequency means a photon of a certain amount of energy. Besides that relationship, a specific kind of atom can only give off certain frequencies of radiation, so it can also only give off photons that have certain amounts of energy.

History

Isaac Newton thought that light was made of very small things that we would now call particles (he referred to them as "Corpuscles"). Christiaan Huygens thought that light was made of waves. Scientists thought that a thing cannot be a particle and a wave at the same time.

Scientists did experiments to find out whether light was made of particles or waves. They found out that both ideas were right — light was somehow both waves and particles. The Double-slit experiment performed by Thomas Young showed that light must act like a wave. The Photoelectric effect discovered by Albert Einstein proved that light had to act like particles that carried specific amounts of energy, and that the energies were linked to their frequencies. This experimental result is called the "wave-particle duality" in quantum mechanics. Later, physicists found out that everything behaves both like a wave and like a particle, not just light. However, this effect is much smaller in large objects.

Here are some of the people who discovered the basic parts of quantum mechanics: Max Planck, Albert Einstein, Satyendra Nath Bose, Niels Bohr, Louis de Broglie, Max Born, Paul Dirac, Werner Heisenberg, Wolfgang Pauli, Erwin Schrödinger, John von Neumann, and Richard Feynman. They did their work in the first half of the 20th century.

Beyond Planck

Quantum mechanics formulae and ideas were made to explain the light that comes from glowing hydrogen. The quantum theory of the atom also had to explain why the electron stays in its orbit, which other ideas were not able to explain. It followed from the older ideas that the electron would have to fall in to the center of the atom because it starts out being kept in orbit by its own energy, but it would quickly lose its energy as it revolves in its orbit. (This is because electrons and other charged particles were known to emit light and lose energy when they changed speed or turned.)

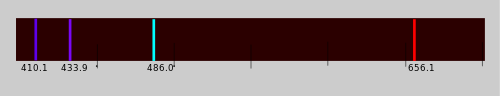

Hydrogen lamps work like neon lamps, but neon lamps have their own unique group of colors (and frequencies) of light. Scientists learned that they could identify all elements by the light colors they produce. They just could not figure out how the frequencies were determined.

Then, a Swiss mathematician named Johann Balmer figured out an equation that told what λ (lambda, for wave length) would be:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda = B\left(\frac{n^2}{n^2-4}\right) \qquad\qquad n = 3,4,5,6 }[/math]

where B is a number that Balmer determined to be equal to 364.56 nm.

This equation only worked for the visible light from a hydrogen lamp. But later, the equation was made more general:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{\lambda} = R \left(\frac{1}{m^2} - \frac{1}{n^2}\right), }[/math]

where R is the Rydberg constant, equal to 0.0110 nm−1, and n must be greater than m.

Putting in different numbers for m and n, it is easy to predict frequencies for many types of light (ultraviolet, visible, and infared). To see how this works, go to Hyperphysics and go down past the middle of the page. (Use H = 1 for hydrogen.)

In 1908, Walter Ritz made the Ritz combination principle that shows how certain gaps between frequencies keep repeating themselves. This turned out to be important to Werner Heisenberg several years later.

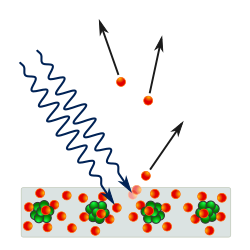

In 1905, Albert Einstein used Planck's idea to show that a beam of light is made up of a stream of particles called photons. The energy of each photon depends on its frequency. Einstein's idea is the beginning of the idea in quantum mechanics that all subatomic particles like electrons, protons, neutrons, and others are both waves and particles at the same time. (See picture of atom with the electron as waves at atom.) This led to a theory about subatomic particles and electromagnetic waves called wave-particle duality. This is where particles and waves were neither one nor the other, but had certain properties of both.

In 1913, Niels Bohr came up with the idea that electrons could only take up certain orbits around the nucleus of an atom. Under Bohr's theory, the numbers called m and n in the equation above could represent orbits. Bohr's theory said electrons could begin in some orbit m and end up in some orbit n, or an electron could begin in some orbit n and end up in some orbit m. If a photon hits an electron, its energy will be absorbed, and the electron will move to a higher orbit because of that extra energy. Under Bohr's theory, if an electron falls from a higher orbit to a lower orbit, then it will have to give up energy in the form of a photon. The energy of the photon will equal the energy difference between the two orbits, and the energy of a photon makes it have a certain frequency and color. Bohr's theory provided a good explanation of many aspects of subatomic phenomena, but failed to answer why each of the colors of light produced by glowing hydrogen (and by glowing neon or any other element) has a brightness of its own, and the brightness differences are always the same for each element.

By the time Niels Bohr came out with his theory, most things about the light produced by a hydrogen lamp were known, but scientists still could not explain the brightness of each of the lines produced by glowing hydrogen.

Werner Heisenberg took on the job of explaining the brightness or "intensity" of each line. He could not use any simple rule like the one Balmer had come up with. He had to use the very difficult math of classical physics that figures everything out in terms of things like the mass (weight) of an electron, the charge (static electric strength) of an electron, and other tiny quantities. Classical physics already had answers for the brightness of the bands of color that a hydrogen lamp produces, but the classical theory said that there should be a continuous rainbow, and not four separate color bands. Heisenberg's explanation is:

There is some law that says what frequencies of light glowing hydrogen will produce. It has to predict spaced-out frequencies when the electrons involved are moving between orbits close to the nucleus (center) of the atom, but it also has to predict that the frequencies will get closer and closer together as we look at what the electron does in moving between orbits farther and farther out. It will also predict that the intensity differences between frequencies get closer and closer together as we go out. Where classical physics already gives the right answers by one set of equations the new physics has to give the same answers but by different equations.

Classical physics uses the mathematical methods of Joseph Fourier to make a math picture of the physical world, It uses collections of smooth curves that go together to make one smooth curve that gives, in this case, intensities for light of all frequencies from some light. But it is not right because that smooth curve only appears at higher frequencies. At lower frequencies, there are always isolated points and nothing connects the dots. So, to make a map of the real world, Heisenberg had to make a big change. He had to do something to pick out only the numbers that would match what was seen in nature. Sometimes people say he "guessed" these equations, but he was not making blind guesses. He found what he needed. The numbers that he calculated would put dots on a graph, but there would be no line drawn between the dots. And making one "graph" just of dots for every set of calculations would have wasted lots of paper and not have gotten anything done. Heisenberg found a way to efficiently predict the intensities for different frequencies and to organize that information in a helpful way.

Just using the empirical rule given above, the one that Balmer got started and Rydberg improved, we can see how to get one set of numbers that would help Heisenberg get the kind of picture that he wanted:

The rule says that when the electron moves from one orbit to another it either gains or loses energy, depending on whether it is getting farther from the center or nearer to it. So we can put these orbits or energy levels in as headings along the top and the side of a grid. For historical reasons the lowest orbit is called n, and the next orbit out is called n - a, then comes n - b, and so forth. It is confusing that they used negative numbers when the electrons were actually gaining energy, but that is just the way it is.

Since the Rydberg rule gives us frequencies, we can use that rule to put in numbers depending on where the electron goes. If the electron starts at n and ends up at n, then it has not really gone anywhere, so it did not gain energy and it did not lose energy. So the frequency is 0. If the electron starts at n-a and ends up at n, then it has fallen from a higher orbit to a lower orbit. If it does so then it loses energy, and the energy it loses shows up as a photon. The photon has a certain amount of energy, e, and that is related to a certain frequency f by the equation e = h f. So we know that a certain change of orbit is going to produce a certain frequency of light, f. If the electron starts at n and ends up at n - a, that means it has gone from a lower orbit to a higher orbit. That only happens when a photon of a certain frequency and energy comes in from the outside, is absorbed by the electron and gives it its energy, and that is what makes the electron go out to a higher orbit. So, to keep everything making sense, we write that frequency as a negative number. There was a photon with a certain frequency and now it has been taken away.

So we can make a grid like this, where f(a←b) means the frequency involved when an electron goes from energy state (orbit) b to energy state a (Again, sequences look backwards, but that is the way they were originally written.):

Grid of f

| Electron States | n | n-a | n-b | n-c | .... | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | f(n←n) | f(n←n-a) | f(n←n-b) | f(n←n-c) | ..... | |

| n-a | f(n-a←n) | f(n-a←n-a) | f(n-a←n-b) | f(n-a←n-c) | ..... | |

| n-b | f(n-b←n) | f(n-b←n-a) | f(n-b←n-b) | f(n-b←n-c) | ..... | |

| transition.... | ..... | ..... | ..... | ..... |

Heisenberg did not make the grids like this. He just did the math that would let him get the intensities he was looking for. But to do that he had to multiply two amplitudes (how high a wave measures) to work out the intensity. (In classical physics, intensity equals amplitude squared.) He made an odd-looking equation to handle this problem, wrote out the rest of his paper, handed it to his boss, and went on vacation. Dr. Born looked at his funny equation and it seemed a little crazy. He must have wondered, "Why did Heisenberg give me this strange thing? Why does he have to do it this way?" Then he realized that he was looking at a blueprint for something he already knew very well. He was used to calling the grid or table that we could write by doing, for instance, all the math for frequencies, a matrix. And Heisenberg's weird equation was a rule for multiplying two of them together. Max Born was a very, very good mathematician. He knew that since the two matrices (grids) being multiplied represented different things (like position (x,y,z) and momentum (mv), for instance), then when you multiply the first matrix by the second you get one answer and when you multiply the second matrix by the first matrix you get another answer. Even though he did not know about matrix math, Heisenberg already saw this "different answers" problem and it had bothered him. But Dr. Born was such a good mathematician that he saw that the difference between the first matrix multiplication and the second matrix multiplication was always going to involve Planck's constant, h, multiplied by the square root of negative one, i. So within a few days of Heisenberg's discovery they already had the basic math for what Heisenberg liked to call the "indeterminacy principle." By "indeterminate" Heisenberg meant that something like an electron is just not pinned down until it gets pinned down. It is a little like a jellyfish that is always squishing around and cannot be "in one place" unless you kill it. Later, people got in the habit of calling it "Heisenberg's uncertainty principle," which made many people make the mistake of thinking that electrons and things like that are really "somewhere" but we are just uncertain about it in our own minds. That idea is wrong. It is not what Heisenberg was talking about. Having trouble measuring something is a problem, but it is not the problem Heisenberg was talking about.

Heisenberg's idea is very hard to grasp, but we can make it clearer with an example. First, we will start calling these grids "matrices," because we will soon need to talk about matrix multiplication.

Suppose that we start with two kinds of measurements, position (q) and momentum (p). In 1925, Heisenberg wrote an equation like this one:

- [math]\displaystyle{ Y(n,n-b) = \sum_{a}^{} \, p(n,n-a)q(n-a,n-b) }[/math] (Equation for the conjugate variables momentum and position)

He did not know it, but this equation gives a blueprint for writing out two matrices (grids) and for multiplying them. The rules for multiplying one matrix by another are a little messy, but here are the two matrices according to the blueprint, and then their product:

Matrix of p

| Electron States | n-a | n-b | n-c | .... | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | p(n←n-a) | p(n←n-b) | p(n←n-c) | ..... | |

| n-a | p(n-a←n-a) | p(n-a←n-b) | p(n-a←n-c) | ..... | |

| n-b | p(n-b←n-a) | p(n-b←n-b) | p(n-b←n-c) | ..... | |

| transition.... | ..... | ..... | ..... | ..... |

Matrix of q

| Electron States | n-b | n-c | n-d | .... | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-a | q(n-a←n-b) | q(n-a←n-c) | q(n-a←n-d) | ..... | |

| n-b | q(n-b←n-b) | q(n-b←n-c) | q(n-b←n-d) | ..... | |

| n-c | q(n-c←n-b) | q(n-c←n-c) | q(n-c←n-d) | ..... | |

| transition.... | ..... | ..... | ..... | ..... |

The matrix for the product of the above two matrices as specified by the relevant equation in Heisenberg's 1925 paper is:

| Electron States | n-b | n-c | n-d | ..... |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | A | ..... | ..... | ..... |

| n-a | ..... | B | ..... | ..... |

| n-b | ..... | ..... | C | ..... |

Where:

A=p(n←n-a)*q(n-a←n-b)+p(n←n-b)*q(n-b←n-b)+p(n←n-c)*q(n-c←n-b)+.....

B=p(n-a←n-a)*q(n-a←n-c)+p(n-a←n-b)*q(n-b←n-c)+p(n-a←n-c)*q(n-c←n-c)+.....

C=p(n-b←n-a)*q(n-a←n-d)+p(n-b←n-b)*q(n-b←n-d)+p(n-b←n-c)*q(n-d←n-d)+.....

and so forth.

If the matrices were reversed, the following values would result:

A=q(n←n-a)*p(n-a←n-b)+q(n←n-b)*p(n-b←n-b)+q(n←n-c)*p(n-c←n-b)+.....

B=q(n-a←n-a)*p(n-a←n-c)+q(n-a←n-b)*p(n-b←n-c)+q(n-a←n-c)*p(n-c←n-c)+.....

C=q(n-b←n-a)*p(n-a←n-d)+q(n-b←n-b)*p(n-b←n-d)+q(n-b←n-c)*p(n-d←n-d)+.....

and so forth.

Note how changing the order of multiplication changes the numbers, step by step, that are actually multiplied.

Beyond Heisenberg

The work of Werner Heisenberg seemed to break a log jam. Very soon, many different other ways of explaining things came from people such as Louis de Broglie, Max Born, Paul Dirac, Wolfgang Pauli, and Erwin Schrödinger.

The math used by Heisenberg and earlier people is not very hard to understand, but the equations quickly grew very complicated as physicists looked more deeply into the atomic world.

Further mysteries

In the early days of quantum mechanics, Albert Einstein suggested that if it were right then quantum mechanics would mean that there would be "spooky action at a distance." It turned out that quantum mechanics was right, and that what Einstein had used as a reason to reject quantum mechanics actually happened. This kind of "spooky connection" between certain quantum events is now called "quantum entanglement".

When an experiment brings two things (photons, electrons, etc.) together, they must then share a common description in quantum mechanics. When they are later separated, they keep the same quantum mechanical description or "state." In the diagram, one characteristic (e.g., "up" spin) is drawn in red, and its mate (e.g., "down" spin) is drawn in blue. The purple band means that when, e.g., two electrons are put together the pair shares both characteristics. So both electrons could show either up spin or down spin. When they are later separated, one remaining on Earth and one going to some planet of the star Alpha Centauri, they still each have both spins. In other words, each one of them can "decide" to show itself as a spin-up electron or a spin-down electron. But if later on someone measures the other one, it must "decide" to show itself as having the opposite spin.

Einstein argued that over such a great distance it was crazy to think that forcing one electron to show its spin would then somehow make the other electron show an opposite characteristic. He said that the two electrons must have been spin-up or spin-down all along, but that quantum mechanics could not predict which characteristic each electron had. Being unable to predict, only being able to look at one of them with the right experiment, meant that quantum mechanics could not account for something important. Therefore, Einstein said, quantum mechanics had a big hole in it. Quantum mechanics was incomplete.

Later, it turned out that experiments showed that it was Einstein who was wrong.[1]

Heisenberg uncertainty principle

In 1925, Werner Heisenberg described the Uncertainty principle, which says that the more we know about where a particle is, the less we can know about how fast it is going and in which direction. In other words, the more we know about the speed and direction of something small, the less we can know about its position. Physicists usually talk about the momentum in such discussions instead of talking about speed. Momentum is just the speed of something in a certain direction times its mass.

The reason behind Heisenberg's uncertainty principle says that we can never know both the location and the momentum of a particle. Because light is an abundant particle, it is used for measuring other particles. The only way to measure it is to bounce the light wave off of the particle and record the results. If a high energy, or high frequency, light beam is used, we can tell precisely where it is, but cannot tell how fast it was going. This is because the high energy photon transfers energy to the particle and changes the particle's speed. If we use a low energy photon, we can tell how fast it is going, but not where it is. This is because we are using light with a longer wavelength. The longer wavelength means the particle could be anywhere along the stretch of the wave.

The principle also says that there are many pairs of measurements for which we cannot know both of them about any particle (a very small thing), no matter how hard we try. The more we learn about one of such a pair, the less we can know about the other.

Even Albert Einstein had trouble accepting such a bizarre concept, and in a well-known debate said, "God does not play dice". To this, Danish physicist Niels Bohr famously responded, "Einstein, don't tell God what to do".

Uses of quantum mechanics

Electrons surround every atom's nucleus. Chemical bonds link atoms to form molecules. A chemical bond links two atoms when electrons are shared between those atoms. Thus quantum mechanics is the physics of the chemical bond and of chemistry. Quantum mechanics helps us understand how molecules are made, and what their properties are.[2]

Quantum mechanics can also help us understand big things, such as stars and even the whole universe. Quantum mechanics is a very important part of the theory of how the universe began called the Big Bang.

Everything made of matter is attracted to other matter because of a fundamental force called gravity. Einstein's theory that explains gravity is called the theory of general relativity. A problem in modern physics is that some conclusions of quantum mechanics do not seem to agree with the theory of general relativity.

Quantum mechanics is the part of physics that can explain why all electronic technology works as it does. Thus quantum mechanics explains how computers work, because computers are electronic machines. But the designers of the early computer hardware of around 1950 or 1960 did not need to think about quantum mechanics. The designers of radios and televisions at that time did not think about quantum mechanics either. However, the design of the more powerful integrated circuits and computer memory technologies of recent years does require quantum mechanics.

Quantum mechanics has also made possible technologies such as:

- Spectroscopy

- Lasers

- MRIs

- CDs and DVDs

Why quantum mechanics is hard to learn

Quantum mechanics is a challenging subject for several reasons:

- Quantum mechanics explains things in very different ways from what we learn about the world when we are children.

- Understanding quantum mechanics requires more mathematics than algebra and simple calculus. It also requires matrix algebra, complex numbers, probability theory, and partial differential equations.

- Physicists are not sure what some of the equations of quantum mechanics tell us about the real world.

- Quantum mechanics suggests that atoms and subatomic particles behave in strange ways, completely unlike anything we see in our everyday lives.

- Quantum mechanics describes things that are extremely small, so we cannot see some of them without special equipment, and we cannot see many of them at all.

Quantum mechanics describes nature in a way that is different from how we usually think about science. It tells us how likely to happen some things are, rather than telling us that they certainly will happen.

One example is Young's double-slit experiment. If we shoot single photons (single units of light) from a laser at a sheet of photographic film, we will see a single spot of light on the developed film. If we put a sheet of metal in between, and make two very narrow slits in the sheet, when we fire many photons at the metal sheet, and they have to go through the slits, then we will see something remarkable. All the way across the sheet of developed film we will see a series of bright and dark bands. We can use mathematics to tell exactly where the bright bands will be and how bright the light was that made them, that is, we can tell ahead of time how many photons will fall on each band. But if we slow the process down and see where each photon lands on the screen we can never tell ahead of time where the next one will show up. We can know for sure that it is most likely that a photon will hit the center bright band, and that it gets less and less likely that a photon will show up at bands farther and farther from the center. So we know for sure that the bands will be brightest at the center and get dimmer and dimmer farther away. But we never know for sure which photon will go into which band.

One of the strange conclusions of quantum mechanics theory is the "Schrödinger's cat" effect. Certain properties of a particle, such as their position, speed of motion, direction of motion, and "spin", cannot be talked about until something measures them (a photon bouncing off of an electron would count as a measurement of its position, for example). Before the measurement, the particle is in a "superposition of states," in which its properties have many values at the same time. Schrödinger said that quantum mechanics seemed to say that if something (such as the life or death of a cat) was determined by a quantum event, then its state would be determined by the state that resulted from the quantum event, but only at the time that somebody looked at the state of the quantum event. In the time before the state of the quantum event is looked at, perhaps "the living and dead cat (pardon the expression) [are] mixed or smeared out in equal parts."[3]

Reduced Planck's constant

People often use the symbol [math]\displaystyle{ \hbar }[/math], which is called "h-bar." [math]\displaystyle{ \hbar=\frac{h}{2\pi} }[/math] . H-bar is a unit of angular momentum. When this new unit is used to describe the orbits of electrons in atoms, the angular momentum of any electron in orbit is always a whole number.[4]

Example

The particle in a 1-dimensional well is the most simple example showing that the energy of a particle can only have specific values. The energy is said to be "quantized." The well has zero potential energy inside a range and has infinite potential energy everywhere outside that range. For the 1-dimensional case in the [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] direction, the time-independent Schrödinger equation can be written as:[5]

- [math]\displaystyle{ - \frac {\hbar ^2}{2m} \frac {d ^2 \psi}{dx^2} = E \psi. }[/math]

Using differential equations, we can figure out that [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] can be written as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \psi = A e^{ikx} + B e ^{-ikx} \;\;\;\;\;\; E = \frac{\hbar^2 k^2}{2m} }[/math]

or as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \psi = C \sin kx + D \cos kx \; }[/math] (by Euler's formula).

The walls of the box mean that the wavefunction must have a special form. The wavefunction of the particle must be zero anytime the walls are infinitely tall. At each wall:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \psi = 0 \; \mathrm{at} \;\; x = 0,\; x = L }[/math]

Consider [math]\displaystyle{ x = 0 }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sin 0 = 0, \cos 0 = 1. }[/math] To satisfy [math]\displaystyle{ \psi = 0 }[/math] the [math]\displaystyle{ \cos }[/math] term has to be removed. Hence [math]\displaystyle{ D = 0 }[/math].

Now consider: [math]\displaystyle{ \psi = C \sin kx\; }[/math]

- at [math]\displaystyle{ x = L }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \psi = C \sin kL =0\; }[/math]

- If [math]\displaystyle{ C = 0 }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \psi =0 \; }[/math] for all x. This solution is not useful.

- therefore [math]\displaystyle{ \sin kL = 0 }[/math] must be true, giving us

- [math]\displaystyle{ kL = n \pi \;\;\;\; n = 1,2,3,4,5,... \; }[/math]

We can see that [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] must be an integer. This means that the particle can only have special energy values and cannot have the energy values in between. This is an example of energy "quantization."

Quantum Mechanics Media

Wave functions of the electron in a hydrogen atom at different energy levels. Quantum mechanics cannot predict the exact location of a particle in space, only the probability of finding it at different locations. The brighter areas represent a higher probability of finding the electron.

An illustration of the double-slit experiment

A simplified diagram of quantum tunneling, a phenomenon by which a particle may move through a barrier which would be impossible under classical mechanics

Position space probability density of a Gaussian wave packet moving in one dimension in free space

The Schrödinger's cat thought experiment can be used to visualize the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, where a branching of the universe occurs through a superposition of two quantum mechanical states.

Max Planck is considered the father of the quantum theory.

Related pages

References

- Feynman, Richard, 1985. The Strange Theory of Light and Matter . Princeton University Press.

- McEvoy, J.P. and Oscar Zarate, 1996. Introducing Quantum Theory. Icon Books.

Notes

- ↑ For an overview of the whole issue of entanglement, see J.P. McEvoy and Oscar Zarate, Introducing Quantum Theory, pp. 168—170.

- ↑ For a good foundation see The Nature of the Chemical Bond, by Linus Pauling.

- ↑ Schrödinger: "The Present Situation in Quantum Mechanics," p. 8 of 22.

- ↑ Scientific American Reader, Simon and Schuster, 1953, p. 117.

- ↑ Derivation of particle in a box, chemistry.tidalswan.com Archived 2007-03-30 at the Wayback Machine

More reading

- Cox, Brian; & Forshaw, Jeff (2011). The Quantum Universe: Everything That Can Happen Does Happen. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-1-84614-432-5

Other websites

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |