Beryllium

Beryllium is in group 2 of the periodic table, so it is an alkaline earth metal. It is grayish (slightly gray) in color. It has an atomic number of 4 and is symbolized by the letters Be. It is toxic and should not be handled without proper training.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| General properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /bəˈrɪliəm/ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | white-gray metallic | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight (Ar, standard) | 9.0121831(5)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beryllium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 2 (alkaline earth metals) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | s-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | alkaline earth metal | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [He] 2s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Electrons per shell | 2, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | Be: Solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1560 K (1287 °C, 2349 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2742 K (2469 °C, 4476 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 1.85 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 1.690 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 5205 K, MPa (extrapolated) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 12.2 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 292 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 16.443 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | +1,[2] +2 (an amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.57 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 112 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 96±3 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 153 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spectral lines of beryllium | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | Be: Primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||

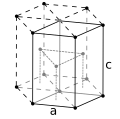

| Crystal structure | hexagonal close-packed (hcp) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 12,890 m/s (at r.t.)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 11.3 µm/(m·K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 200 W/(m·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 36 nΩ·m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic susceptibility | −9.0·10−6 cm3/mol[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 287 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 132 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 130 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.032 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 5.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 1670 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 590–1320 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-41-7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Louis Nicolas Vauquelin (1798) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Friedrich Wöhler & Antoine Bussy (1828) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of beryllium | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Beryllium has 4 electrons, 4 protons, and 5 neutrons.

Beryllium has one of the highest melting points of the light metals: 1560 K (1287 °C). It is added to other metals to make stronger alloys. Beryllium-copper alloy is used in tools because it does not make sparks.

At standard temperature and pressure, beryllium resists oxidation when exposed to oxygen.

Beryllium is best known for the chemical compounds it forms. Beryllium combines with aluminium, silicon and oxygen to make a mineral called beryl. Emerald and aquamarine are two varieties of beryl which are used as gemstones in jewelry.

Since it has a very high stiffness to weight ratio, beryllium is used to make the diaphragms in some high-end speakers.

Uses

Beryllium is used to make jet aircrafts, guided missiles, spacecraft, and satellites, including the James Webb telescope.[6][7] Beryllium can reflect neutrons, and thin foils of beryllium are sometimes used in nuclear weapons as the outer layer of the plutonium pits.[8] Beryllium is also used in fuel rods for CANDU reactors. Beryllium is used to make many dental alloys.[6][7]

Rarity

It is a relatively rare element in the universe. It usually occurs when larger atomic nuclei have split up. In stars, beryllium is depleted because it is fused and builds larger elements.

Beryllium Media

Beryllium ore with a U.S. penny for scale

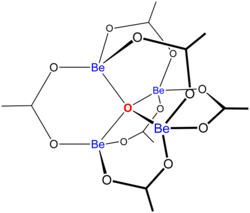

Schematic structure of basic beryllium acetate

Louis-Nicolas Vauquelin discovered beryllium

Friedrich Wöhler was one of the men who independently isolated beryllium

Related pages

References

- ↑ Meija, J.; Coplen, T. B.; Berglund, M.; Brand, W.A.; De Bièvre, P.; Gröning, M.; Holden, N.E.; Irrgeher, J.; Loss, R.D.; Walczyk, T.; Prohaska, T. (2016). "Atomic weights of the elements 2013 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 88 (3): 265–91. doi:10.1515/pac-2015-0305.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Beryllium: Beryllium(I) Hydride compound data" (PDF). bernath.uwaterloo.ca. Retrieved 2007-12-10. }}

- ↑ Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 14.48. ISBN 1439855110.

- ↑ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ↑ "Beryllium: Beryllium(I) Hydride compound data" (PDF). bernath.uwaterloo.ca. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Metals handbook. Davis, J. R. (Joseph R.), ASM International. Handbook Committee. (Desk ed., 2nd ed.). Materials Park, Oh.: ASM International. 1998. ISBN 0-87170-654-7. OCLC 40452949.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 Schwartz, Mel M. (2002). Encyclopedia of materials, parts, and finishes (2nd ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 1-56676-661-3. OCLC 48907078.

- ↑ Barnaby, Frank. (1993). How nuclear weapons spread : nuclear-weapon proliferation in the 1990s. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-16832-1. OCLC 252789074.