Universe

The universe is space and everything in it.[1][2][3][4] It is made of many billions of stars and planets and enormous clouds of gas separated by big spaces. The Big Bang started the expansion of the universe.

Astronomers use telescopes to look at distant galaxies. This is how they see what the universe looked like a long time ago. The past tense is because the light from distant parts of the Universe takes a very long time to reach us. From these observations, it seems the physical laws and constants of the universe have not changed.

Physicists are currently unsure if anything existed before the Big Bang. The size of the universe is not known.

History

People have long had ideas about the universe. They saw the sky at night, with fixed stars and other stars moving among them. Most early ideas had the Earth at the center of the universe. This is known as geocentrism.

Some ancient Greeks thought that the universe has infinite space and has existed forever. They thought it had a set of celestial spheres which corresponded to the fixed stars, the Sun and various planets. The spheres circled about a round but unmoving Earth.

Over hundreds of years, better observations led to Copernicus's Sun-centered model, known as heliocentrism. This was very controversial at the time, and was fought by religious authorities, most famously by the Christian church (see Giordano Bruno and Galileo).

The invention of the telescope in the Netherlands, 1608, was a very important moment in astronomy. By the middle of the 1800s, telescopes were good enough for other galaxies to be seen. The modern optical (uses visible light) telescope is still more advanced. Meanwhile, Isaac Newton improved the ideas of gravity and dynamics (equations) and showed how the Solar System worked.

In the 1900s, better telescopes showed astronomers more about the universe. The Solar System is in a galaxy made of billions of stars, which we call the Milky Way. Other galaxies exist outside it, as far as we can see. This started a new kind of astronomy called cosmology, in which astronomers study what these galaxies are made of and how they are spread out. By measuring the redshift of galaxies, cosmologists soon discovered that the Universe is expanding (see: Hubble).

Big Bang

The most used scientific model of the Universe is known as the Big Bang theory, which says the Universe expanded from a single point that held all the matter and energy of the Universe. There are many kinds of scientific evidence that support the Big Bang idea. Astronomers think that the Big Bang happened about 13.73 billion years ago.[5] this would make the universe 13.73 billion years old. Since then, the universe has expanded to be at least 93 billion light years, or 8.80 ×1026 meters, in diameter. It is still expanding right now, and the expansion is getting faster.

Astronomers are not sure what is causing the universe to expand. Because of this, they call the mysterious energy causing the expansion dark energy. By studying the expansion of the Universe, astronomers have also realized most of the matter in the Universe may be in a form which cannot be observed by any scientific equipment we have. This matter has been named dark matter. Just to be clear, dark matter and energy have not been observed directly (that is why they are called 'dark'). However, many astronomers think they must exist: many astronomical observations would be hard to explain if they didn't.

Some parts of the universe are expanding even faster than the speed of light. This means the light will never be able to reach us here on Earth, so we will never be able to see these parts of the universe. We call the part of the universe we can see the observable universe.

History of the term "universe"

The word universe comes from the Old French word universe, which comes from the Latin word universe.[6] The Latin word was used by Cicero and later Latin authors in many of the same senses as the modern English word is used.

A different theory is an early Greek model of the universe. In that model, all matter was in rotating spheres centered on the Earth; according to Aristotle, the rotation of the outermost sphere was responsible for the motion and change of everything within. It was natural for the Greeks to assume that the Earth was stationary and that the heavens rotated about the Earth, because careful astronomical and physical measurements are needed to prove otherwise.

The most common term for "universe" among the ancient Greek philosophers from Pythagoras onwards was το παν (The All), defined as all matter (το ολον) and all space (το κενον).[7]

Broadest meaning

The broadest word meaning of the Universe is found in De division naturae by the medieval philosopher Johannes Scotus Erigena, who defined it as simply everything: everything that exists and everything that does not exist.

Definition as reality

Usually the universe is thought to be everything that exists, has existed, and will exist.[8] This definition says that the universe is made of two elements: space and time, together known as space-time or the vacuum; and matter and different forms of energy and momentum occupying space-time. The two kinds of elements behave according to physical laws, in which we describe how the elements interact.

A similar definition of the term universe is everything that exists at a single moment of time, such as the present or the beginning of time.

In Aristotle's book The Physics, Aristotle divided το παν (everything) into three roughly analogous elements: matter (the stuff of which the universe is made), form (the arrangement of that matter in space) and change (how matter is created, destroyed or altered in its properties, and similarly, how form is altered). Physical laws were the rules governing the properties of matter, form and their changes. Later philosophers such as Lucretius, Averroes, Avicenna and Baruch Spinoza altered or refined these divisions. For example, Averroes and Spinoza have active principles governing the universe which act on passive elements.

Space-time definitions

It is possible to form space-times, each existing but not able to touch, move, or change (interact with each other. The entire collection of these separate space-times is denoted as the multiverse.[9] In principle, the other unconnected universes may have different dimensionalities and topologies of space-time, different forms of matter and energy, and different physical laws and physical constants, although such possibilities are speculations.

Observable reality

According to a still-more-restrictive definition, the Universe is everything within our connected space-time that could have a chance to interact with us and vice versa.

According to the general idea of relativity, some regions of space may never interact with ours even in the lifetime of the Universe, due to the finite speed of light and the ongoing expansion of space. For example, radio messages sent from Earth may never reach some regions of space, even if the Universe would exist forever; space may expand faster than light can traverse it.

It is worth emphasizing that those distant regions of space are taken to exist and be part of reality as much as we are; yet we can never interact with them, even in principle. Even with most of the visible universe, we cannot interact with it in practice. A relatively simple task, so it might seem, would be to communicate within our galaxy. Even if we knew how to send a message successfully, it would be well over 200,000 years before a reply could come back from the far end of the Milky Way, whose diameter is 100,000 light years. galaxy. The spatial region which we can see is called the observable universe.

Basic data on the universe

The Universe is huge. The matter which can be seen is spread over a space at least 93 billion light years across.[10]

For comparison, the diameter of a typical galaxy is only 30,000 light-years, and the typical distance between two neighboring galaxies is only 3 million light-years.[11] As an example, our Milky Way Galaxy is roughly 100,000 light years in diameter,[12] and our nearest sister galaxy, the Andromeda Galaxy, is roughly 2.5 million light years away.[13] The observable Universe contains more than 2 trillion (1012) galaxies[14] and, overall, as many as an estimated 1×1024 stars[15][16] (more stars than all the grains of sand on planet Earth).[17]

Typical galaxies range from dwarf galaxies with as few as ten million (107) stars up to giants with one trillion[18] (1012) stars, all orbiting the galaxy's center of mass. Thus, a rough estimate from these numbers would suggest there are around one sextillion (1021) stars in the observable Universe; though a 2003 study by Australian National University astronomers resulted in a figure of 70 sextillion (7 x 1022).[19]

The matter that can be seen is spread throughout the Universe when averaged over distances longer than 300 million light-years.[20] However, on smaller length-scales, matter is observed to form 'clumps', many atoms are condensed into stars, most stars into galaxies, most galaxies into galaxy groups and clusters and, lastly, the largest-scale structures such as the Great Wall of galaxies.

The present overall density of the Universe is very low, roughly 9.9 × 10−30 grams per cubic centimetre. This mass-energy appears to consist of 73% dark energy, 23% cold dark matter and 4% ordinary matter. The density of atoms is about a single hydrogen atom for every four cubic meters of volume.[21] The properties of dark energy and dark matter are not known. Dark matter slows the expansion of the universe. Dark energy makes its expansion faster.

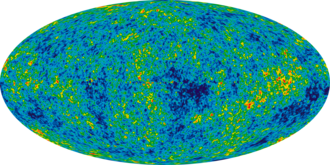

The Universe is old, and changing. The best good guess of the Universe's age is 13.798±0.037 billion years old, based on the cosmic microwave background radiation.[22][23][24] Independent estimates (based on measurements such as radioactive dating) agree, although they are less precise, ranging from 11 to 20 billion years.[25] to 13–15 billion years.[26]

The Universe has not been the same at all times in its history. Its getting bigger accounts for how Earth-bound people can see the light from a galaxy 30 billion light-years away, even if that light has traveled for only 13 billion years; the very space between them has expanded. This expansion is consistent with the observation that the light from distant galaxies has been redshifted; the photons emitted have been stretched to longer wavelengths and lower frequency during their journey. The rate of this spatial expansion is accelerating, based on studies of Type Ia supernovae and other data.

The relative amounts of different chemical elements — especially the lightest atoms such as hydrogen, deuterium and helium — seem to be identical in all of the Universe and throughout all of the history of it that we know of.[27] The Universe seems to have much more matter than antimatter.[28] The Universe appears to have no net electric charge. Gravity is the dominant interaction at cosmological distances. The Universe also seems to have no net momentum or angular momentum. The absence of net charge and momentum is expected if the Universe is finite.[29]

The Universe appears to have a smooth space-time continuum made of three spatial dimensions and one temporal (time) dimension. On the average, space is very nearly flat (close to zero curvature), meaning that Euclidean geometry is experimentally true with high accuracy throughout most of the Universe.[30] However, the Universe may have more dimensions, and its spacetime may have a multiply connected global topology.[31]

As far as we can tell, the Universe has the same physical laws and physical constants throughout.[32] According to the prevailing Standard Model of physics, all matter is composed of three generations of leptons and quarks, both of which are fermions. These elementary particles interact via at most three fundamental interactions: the electroweak interaction which includes electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force; the strong nuclear force described by quantum chromodynamics; and gravity, which is best described at present by general relativity.

Special relativity holds in all the universe in local space and time. Otherwise, general relativity holds. There is no explanation for the particular values that physical constants appear to have throughout our universe, such as Planck's constant h or the gravitational constant G. Several conservation laws have been identified, such as the conservation of charge, conservation of momentum, conservation of angular momentum and conservation of energy.

Theoretical models

General theory of relativity

Accurate predictions of the universe's past and future require an accurate theory of gravitation. The best theory available is Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity, which has passed all experimental tests so far. However, since rigorous experiments have not been carried out on cosmological length scales, general relativity could conceivably be inaccurate. Nevertheless, its predictions appear to be consistent with observations, so there is no reason to adopt another theory.

General relativity provides of a set of ten nonlinear partial differential equations for the spacetime metric (Einstein's field equations) that must be solved from the distribution of mass-energy and momentum throughout the universe. Since these are unknown in exact detail, cosmological models have been based on the cosmological principle, which states that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic. In effect, this principle asserts that the gravitational effects of the various galaxies making up the universe are equivalent to those of a fine dust distributed uniformly throughout the universe with the same average density. The assumption of a uniform dust makes it easy to solve Einstein's field equations and predict the past and future of the universe on cosmological time scales.

Einstein's field equations include a cosmological constant (Lamda: Λ),[33][34] that is related to an energy density of empty space.[35] Depending on its sign, the cosmological constant can either slow (negative Λ) or accelerate (positive Λ) the expansion of the Universe. Although many scientists, including Einstein, had speculated that Λ was zero,[36] recent astronomical observations of type Ia supernovae have detected a large amount of dark energy that is accelerating the Universe's expansion.[37] Preliminary studies suggest that this dark energy is related to a positive Λ, although alternative theories cannot be ruled out as yet.[38]

Big Bang model

The prevailing Big Bang model accounts for many of the experimental observations described above, such as the correlation of distance and redshift of galaxies, the universal ratio of hydrogen:helium atoms, and the ubiquitous, isotropic microwave radiation background. As noted above, the redshift arises from the metric expansion of space; as the space itself expands, the wavelength of a photon traveling through space likewise increases, decreasing its energy. The longer a photon has been traveling, the more expansion it has undergone; hence, older photons from more distant galaxies are the most red-shifted. Determining the correlation between distance and redshift is an important problem in experimental physical cosmology.

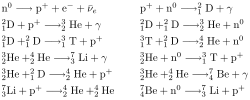

Other experimental observations can be explained by combining the overall expansion of space with nuclear physics and atomic physics. As the Universe expands, the energy density of the electromagnetic radiation decreases more quickly than does that of matter, since the energy of a photon decreases with its wavelength. Thus, although the energy density of the Universe is now dominated by matter, it was once dominated by radiation; poetically speaking, all was light. As the Universe expanded, its energy density decreased and it became cooler; as it did so, the elementary particles of matter could associate stably into ever larger combinations. Thus, in the early part of the matter-dominated era, stable protons and neutrons formed, which then associated into atomic nuclei. At this stage, the matter in the Universe was mainly a hot, dense plasma of negative electrons, neutral neutrinos and positive nuclei. Nuclear reactions among the nuclei led to the present abundances of the lighter nuclei, particularly hydrogen, deuterium, and helium. Eventually, the electrons and nuclei combined to form stable atoms, which are transparent to most wavelengths of radiation; at this point, the radiation decoupled from the matter, forming the ubiquitous, isotropic background of microwave radiation observed today.

Other observations are not clearly answered by known physics. According to the prevailing theory, a slight imbalance of matter over antimatter was present in the universe's creation, or developed very shortly thereafter. Although the matter and antimatter mostly annihilated one another, producing photons, a small residue of matter survived, giving the present matter-dominated universe.

Several lines of evidence also suggest that a rapid cosmic inflation of the universe occurred very early in its history (roughly 10−35 seconds after its creation). Recent observations also suggest that the cosmological constant (Λ) is not zero, and that the net mass-energy content of the universe is dominated by a dark energy and dark matter that have not been characterized scientifically. They differ in their gravitational effects. Dark matter gravitates as ordinary matter does, and thus slows the expansion of the universe; by contrast, dark energy serves to accelerate the universe's expansion.

Multiverse hypothesis

Some people think that there is more than one universe. They think that there is a set of universes called the multiverse.

By definition, there is no way for anything in one universe to affect something in another. The multiverse is not yet a scientific idea because there is no way to test it. An idea that cannot be tested or is not based on logic is not science. It is not known if the multiverse is a scientific idea.

Future

This is a scientific topic called "the ultimate fate of the universe". It is a topic in cosmology. There are possible scenarios for its evolution. The basic issue is whether its existence is finite or infinite.

The future of the universe is a mystery. However, there are a couple of theories based on the possible shapes of the universe:[39]

- If the universe is a closed sphere, it will stop expanding. The universe will do the opposite of that and become a singularity for another Big Bang. This is the Big Crunch or Big Bounce theory.

- If the universe is an open sphere, it will speed up the expansion. After 22,000,000,000 (22 billion) years, the universe will rip apart with the force. This is the Big Rip theory.

- If the universe is flat, it will expand forever. All stars will lose their energy.

- After a googol years, the black holes will also be gone. This is the heat death of the universe, or Big Freeze theory.

There is a consensus among cosmologists that the shape of the universe is considered "flat" (parallel lines stay parallel) and will continue to expand forever.[40][41]

Further reading

- Adams, Fred; Gregory Laughlin (2000). The Five Ages of the Universe: Inside the Physics of Eternity. Simon & Schuster Australia. ISBN 978-0-684-86576-8.

- Chaisson, Eric (2001). Cosmic Evolution: The Rise of Complexity in Nature. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00342-2.

- Dyson, Freeman (2004). Infinite in All Directions (the 1985 Gifford Lectures). Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-039081-5.

- Harrison, Edward (2003). Masks of the Universe: Changing Ideas on the Nature of the Cosmos. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77351-5.

- Mack, Katie (2020). The End of Everything: (Astrophysically Speaking). Scribner. ISBN 978-1982103545.

- Penrose, Roger (2004). The Road to Reality. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-45443-4.

- Prigogine, Ilya (2003). Is Future Given?. World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 978-981-238-508-6.

- Smolin, Lee (2001). Three Roads to Quantum Gravity: A New Understanding of Space, Time and the Universe. Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-1261-7.

- Morris, Richard (1982). The Fate of the Universe. Playboy Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-87223-748-6

- Islam, Jamal N. (1983). The Ultimate Fate of the Universe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 978-0521-24814-3

Universe Media

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field, is an image of a small region of space in the constellation Fornax, composited from Hubble Space Telescope data accumulated over a period from September 3, 2003 through January 16, 2004. The patch of sky in which the galaxies reside was chosen because it had a low density of bright stars in the near-field.

Hubble Space Telescope – Ultra-Deep Field galaxies to Legacy field zoom out(video 00:50; May 2, 2019)

In this schematic diagram, time passes from left to right, with the universe represented by a disk-shaped "slice" at any given time. Time and size are not to scale. To make the early stages visible, the time to the afterglow stage (really the first 0.003%) is stretched and the subsequent expansion (really by 1,100 times to the present) is largely suppressed.

Illustration of the observable universe, centered on the Sun. The distance scale is logarithmic. Due to the finite speed of light, we see more distant parts of the universe at earlier times.

The formation of clusters and large-scale filaments in the cold dark matter model with dark energy. The frames show the evolution of structures in a 43 million parsecs (or 140 million light-years) box from redshift of 30 to the present epoch (upper left z=30 to lower right z=0).

A map of the superclusters and voids nearest to Earth

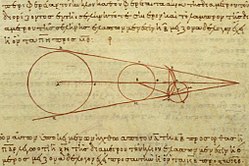

3rd century BCE calculations by Aristarchus on the relative sizes of, from left to right, the Sun, Earth, and Moon, from a 10th-century AD Greek copy

Related pages

References

- ↑ Universe. Webster's New World College Dictionary, Wiley Publishing. 2010.

- ↑ "Universe". Dictionary.com.

- ↑ "Universe". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ↑ Zeilik, Michael; Gregory, Stephen A. (1998). Introductory Astronomy & Astrophysics (4th ed.). Saunders College Publishing. ISBN 0030062284.

The totality of all space and time; all that is, has been, and will be.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (2008-03-09). "Gauging Age of Universe Becomes More Precise". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/09/science/space/09cosmos.html. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ↑ The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, volume II, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971, p.3518.

- ↑ Liddell and Scott, pp.1345–1346.

- ↑ Andrew Liddle, Jon Loveday (9 April 2009). The Oxford companion to cosmology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956084-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ Ellis G.F.R; Kirchner U. & Stoeger W.R. 2004 (2004). "Multiverses and physical cosmology". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 347 (3): 921–936. arXiv:astro-ph/0305292. Bibcode:2004MNRAS.347..921E. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.07261.x. ISSN 0035-8711. S2CID 119028830.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Lineweaver, Charles; Tamara M. Davis (2005). "Misconceptions about the Big Bang". Scientific American. Retrieved 2007-03-05.

- ↑ Rindler (1977), p.196.

- ↑ Christian, Eric; Samar, Safi-Harb. "How large is the Milky Way?". Retrieved 2007-11-28.

- ↑ I. Ribas; et al. (2005). "First Determination of the Distance and Fundamental Properties of an Eclipsing Binary in the Andromeda Galaxy". Astrophysical Journal. 635 (1): L37–L40. arXiv:astro-ph/0511045. Bibcode:2005ApJ...635L..37R. doi:10.1086/499161. S2CID 119522151.

McConnachie A.W.; et al. (2005). "Distances and metallicities for 17 Local Group galaxies". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 356 (4): 979–997. arXiv:astro-ph/0410489. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.356..979M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.08514.x. - ↑ Fountain, Henry (17 October 2016). "Two trillion galaxies, at the very least". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/18/science/two-trillion-galaxies-at-the-very-least.html. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ↑ Staff (2019). "How Many Stars Are There In The Universe?". European Space Agency. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ↑ Marov, Mikhail Ya. (2015). "The Structure of the Universe". The Fundamentals of Modern Astrophysics. pp. 279–294. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-8730-2_10. ISBN 978-1-4614-8729-6.

- ↑ Mackie, Glen (1 February 2002). "To see the Universe in a grain of sand". Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ "Hubble's largest galaxy portrait offers a new high-definition view". NASA. 2006-02-28. Retrieved 2007-01-03.

- ↑ "Star count: ANU Astronomer makes best yet". 2003-07-17. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

- ↑ N. Mandolesi P.; et al. (1986). "Large-scale homogeneity of the Universe measured by the microwave background". Letters to Nature. 319 (6056): 751–753. Bibcode:1986Natur.319..751M. doi:10.1038/319751a0. S2CID 4349689.

- ↑ Hinshaw, Gary (February 10, 2006). "What is the Universe made of?". NASA WMAP. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ↑ "Five-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Data Processing, Sky Maps, and Basic Results" (PDF). nasa.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-10. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ↑ Planck Collaboration (2013). "Planck2013 results. I. Overview of products and scientific results". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 571: A1. arXiv:1303.5062. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321529. S2CID 218716838.

- ↑ Bennett, C.L.; et al. (2013). "Nine-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe ( Wmap ) Observations: Final Maps and Results". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 208 (2): 20. arXiv:1212.5225. Bibcode:2013ApJS..208...20B. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/208/2/20. S2CID 119271232.

- ↑ Britt RR (2003-01-03). "Age of Universe revised, again". space.com. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ↑ Wright E.L. (2005). "Age of the Universe". UCLA. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

Krauss L.M. & Chaboyer B. (2003). "Age Estimates of globular clusters in the Milky Way: constraints on cosmology". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 299 (5603): 65–69. Bibcode:2003Sci...299...65K. doi:10.1126/science.1075631. PMID 12511641. S2CID 10814581. Retrieved 2007-01-08. - ↑ Wright, Edward L. (2004). "Big Bang Nucleosynthesis". UCLA. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

M. Harwit, M. Spaans (2003). "Chemical composition of the early Universe". The Astrophysical Journal. 589 (1): 53–57. arXiv:astro-ph/0302259. Bibcode:2003ApJ...589...53H. doi:10.1086/374415. S2CID 6723861.

C. Kobulnicky & E.D. Skillman (1997). "Chemical composition of the early Universe". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 29: 1329. Bibcode:1997AAS...191.7603K. - ↑ "Antimatter". Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council. October 28, 2003. Archived from the original on 2004-03-07. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ↑ Landau and Lifshitz (1975). p. 361.

- ↑ WMAP Mission: Results – Age of the Universe

- ↑ Luminet, Jean-Pierre (1999). "Topology of the Universe: theory and observations". .

Luminet, J-P.; et al. (2003). "Dodecahedral space topology as an explanation for weak wide-angle temperature correlations in the cosmic microwave background". Nature. 425 (6958): 593–595. arXiv:astro-ph/0310253. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..593L. doi:10.1038/nature01944. PMID 14534579. S2CID 4380713. - ↑ Strobel, Nick (May 23, 2001). "The composition of stars". Astronomy Notes. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

"Have physical constants changed with time?". Astrophysics (Astronomy Frequently Asked Questions). Retrieved 2007-01-04. - ↑ Einstein A. (1917). "Kosmologische Betrachtungen zur allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie". Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Sitzungsberichte 1917 (part 1): 142–152.

- ↑ Rindler (1977), pp. 226–229.

- ↑ Landau and Lifshitz (1975), pp. 358–359.

- ↑ Einstein, A (1931). "Zum kosmologischen Problem der allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie". Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Physikalisch-mathematische Klasse. 1931: 235–237.

Albert Einstein; Willem de Sitter (1932). "On the relation between the expansion and the mean density of the Universe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 18 (3): 213–214. Bibcode:1932PNAS...18..213E. doi:10.1073/pnas.18.3.213. PMC 1076193. PMID 16587663. - ↑ Hubble Telescope news release

- ↑ BBC News story: Evidence that dark energy is the cosmological constant

- ↑ Woollaston, Victoria (2016-10-10). "A big freeze, rip or crunch: how will the universe end?". Wired UK. . https://www.wired.co.uk/article/how-will-universe-end. Retrieved 2019-03-15.

- ↑ "WMAP- Shape of the Universe". map.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ↑ "WMAP- Fate of the Universe". map.gsfc.nasa.gov.

Other websites

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

- Is there a hole in the universe? at HowStuffWorks

- Age of the Universe at Space.Com

- Stephen Hawking's Universe Archived 2016-05-06 at the Wayback Machine – Why is the universe the way it is?

- Cosmology FAQ

- Cosmos – An "illustrated dimensional journey from microcosmos to macrocosmos" Archived 2008-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Illustration comparing the sizes of the planets, the sun, and other stars

- Logarithmic Maps of the Universe Archived 2009-01-24 at the Wayback Machine

- My So-Called Universe Archived 2010-12-25 at the Wayback Machine – Arguments for and against an infinite and parallel universes

- Parallel Universes Archived 2009-04-27 at the Wayback Machine by Max Tegmark

- The Dark Side and the Bright Side of the Universe Princeton University, Shirley Ho

- Richard Powell: An Atlas of the Universe – Images at various scales, with explanations

- Multiple Big Bangs

- Universe – Space Information Centre Archived 2008-03-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Exploring the Universe Archived 2013-04-17 at the Wayback Machine at Nasa.gov

Videos

- The Known Universe created by the American Museum of Natural History