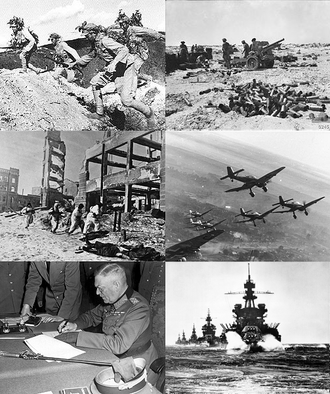

World War II

World War II (WWII or WW2), in the Soviet Union, the Great Patriotic War, and in Japan, the Second Sino-Japanese War, was a global war involving fighting in most of the world and most countries. Most countries fought in the years 1939–1945 but some started fighting in 1937. Most of the world's countries, including all the great powers, fought as part of two military alliances: the Allies and the Axis Powers. World War II was the largest and deadliest conflict in all of history. It involved more countries, cost more money, involved more people, and killed more people than any other war in history.[1] Between 50 to 85 million people died.[2][3] The majority were civilians. It included massacres, the deliberate genocide of the Holocaust, strategic bombing, starvation, disease, and the only use of nuclear weapons against civilians in history.

The two sides were the Allies (at first China, France and Britain, joined by the Soviet Union, United States and others) and the Axis (Germany, Italy and Japan). The war in Asia began when Japan invaded China on July 7, 1937.[4] The war began in Europe when Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. France and Britain reacted by declaring war on Germany. By 1941, much of Europe was under German control, including France. Only Britain remained fighting against the Axis in North Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Atlantic. Germany gave up plans to invade Britain after losing an airplane battle. In June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union, starting the largest area of war in history. On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor and invaded British and French colonies in Asia, and the two wars became one.

The Japanese victories were stopped in 1942, and in that same year the Soviets won the huge Battle of Stalingrad. After that, the Allies started to fight back from all sides. The Axis were forced back in the Soviet Union, lost North Africa, and, starting in 1943, were forced to defend Italy.[5] In 1944, the Allies invaded France, and came into Germany from the west,[6] while the Soviets came in from the east. Germany surrendered on 8 May 1945. Japan formally surrendered on September 2, 1945. The war ended with the Allied victory.

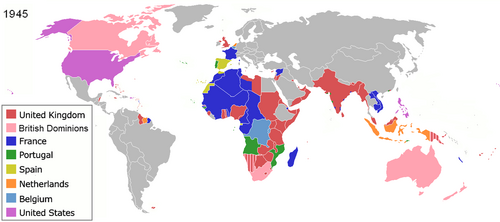

After the war, the United Nations was set up to develop support between countries and to prevent future wars. The Cold War among the major winners soon started, but they did not fight each other in an actual war. Decolonization of Asia and Africa, where those countries controlled by European countries were given their independence, happened as well. This was because European power was weakened from the war. Economic recovery and the political integration (the process of uniting countries) were among other results of the war.

The two sides

The countries that joined the war were on one of two sides: the Axis and the Allies.

The Axis Powers at the start of the war were Germany, Italy and Japan. There were many meetings to create the alliance between these countries.[7][8][9][10] Finland, Slovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Thailand joined the Axis later. As the war continued, some Axis countries changed to join the Allies instead, such as Italy.

The Allied Powers were the United Kingdom and some Commonwealth members, France, Poland, Yugoslavia, Greece, Belgium and China at the start of the war. China had been fighting a civil war. In June 1941, Germany attacked the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa. In December 1941 came Japan's Attack on Pearl Harbor against the United States. These two large, powerful countries then joined the Allies.

Background

World War I had greatly changed the way of diplomacy and politics in Asia, Europe, and Africa with the defeat of the Central Powers. Empires which sided with the Central Powers were destroyed. The Russian Empire, which did not side with the Central Powers, died as well. The war also changed the borders in Eastern Europe, with many new countries born. The war led to strong irredentism and revanchism. These senses were especially strong in Germany, which had no choice but to sign the Treaty of Versailles.[11] The Germans also had 13% of their homeland area and all colonies taken away, and they had to pay back a very large sum of money to the Allies.[12] The size of their army and navy was also limited,[13] while its air force was banned.

In Italy, nationalists were unhappy with the outcome of the war, thinking that their country should have gained far more territory from the past agreement with the Allies. The fascist movement in the 1920s brought Mussolini to the leadership of the country. He promised to make Italy a great power by creating its colonial empire.[14]

After the Kuomintang (KMT), the governing party of China, unified the country in the 1920s, the civil war between it and its past ally Communist Party of China began.[15] In 1931, Japan used the Mukden Incident as a reason to take Manchuria and set up its puppet state, Manchukuo,[16] while the League of Nations could not do anything to stop it. The Tanggu Truce, a ceasefire, was signed in 1933. In 1936, the KMT and the communists agreed to stop fighting against each other to fight Japan instead.[17] In 1937, Japan started a Second Sino-Japanese War to take the rest of China.[18]

After the German Empire was disestablished, the democratic Weimar Republic was set up. There were disagreements between the Germans which involved many political ideologies, ranging from nationalism to communism. The fascist movement in Germany rose because of the Great Depression. Adolf Hitler, leader of the Nazi Party, became the Chancellor in 1933. After the Reichstag fire, Hitler created a totalitarian state, where there is only one party by law.[19] Hitler wanted to change the world order and quickly rebuilt the army, navy and air force,[20] especially after Saarland was reunited in 1935. In March 1936, Hitler sent the army to Rhineland. The Spanish Civil War began in July 1936. The war ended with the nationalist victory, supported by Italy and Germany.

In March 1938, Germany sent its army into Austria, known as the Anschluss, which had only a little reaction from European countries.[21] Shortly after that, the Allies agreed to give Sudetenland, part of Czechoslovakia, to Germany, so that Hitler would promise to stop taking more land.[22] But the rest of the country was either forced to surrender[23] or invaded by March 1939.[24] The Allies now tried to stop him, by promising to help Poland if it was attacked.[25] Just before the war, Germany and the Soviet Union signed a peace agreement, agreeing that they would not attack each other for ten years.[26] In the secret part of it, they agreed to divide Eastern Europe between them.[27]

Course of the war

War breaks out

World War II began on September 1, 1939, as Germany invaded Poland. On September 3, Britain, France, and the members of the Commonwealth declared war on Germany. They could not help Poland much and only sent a small French attack on Germany from the West.[28] The Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland soon after Germany, on September 17.[29] Finally, Poland was divided.

Germany then signed an agreement to work together with the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union forced the Baltic countries to allow it to keep Soviet soldiers in their countries.[30] Finland did not accept the Soviet call for its land, so it was attacked in November 1939.[31] With peace, the world war broke out.[32] France and Britain thought that the Soviet Union might enter the war on the side of Germany and drove the Soviet Union out of the League of Nations.[33]

After Poland was defeated, the "Phoney War" began in Western Europe. While British soldiers were sent to the Continent, there were no big battles fought between two sides.[34] Then, in April 1940, Germany decided to attack Norway and Denmark so that it would be safer to transport iron ore from Sweden. The British and French sent an army to disrupt the German occupation, but had to leave when Germany invaded France.[35] Chamberlain was replaced by Churchill as Prime Minister of United Kingdom in May 1940 because the British were unhappy with his work.[36]

Axis early victories

On 10 May, Germany invaded France, Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg and quickly defeated them by using blitzkrieg tactics.[37] The British were forced to leave mainland Europe at Dunkirk. On June 10, Italy invaded France, declaring war on France and the United Kingdom. Soon after that, France was divided into occupation zones. One was directly controlled by Germany and Italy,[38] and the other was unoccupied Vichy France.

By June 1940, the Soviet Union moved its soldiers into the Baltic states and took them,[39] followed by Bessarabia in Romania. Although there had been some collaboration between the Soviet Union and Germany earlier, this event made it serious.[40][41] Later, when the two could not agree to work more closely together, relationships between them became worse to the point of war.[42]

Then Germany began an air battle over Britain to prepare for a landing on the island,[43] but the plan was finally canceled in September. The German Navy destroyed many British ships transporting goods in the Atlantic.[44] Italy, by this time, had begun its operation in the Mediterranean. The United States remained neutral but started to help the Allies. By helping to protect British ships in the Atlantic, the United States found itself fighting German ships by October 1941 but this was not officially war.[45]

In September 1940, Italy began to invade British-held Egypt. In October, Italy invaded Greece, but it only resulted in an Italian retreat to Albania.[46] Again, in early 1941, an Italian army was pushed from Egypt to Libya in Africa. Germany soon helped Italy. Under Rommel's command, by the end of April 1941, the Commonwealth army was pushed back to Egypt again.[47] Other than North Africa, Germany also successfully invaded Greece, Yugoslavia and Crete by May.[48] Despite these victories, Hitler decided to cancel the bombing of Britain after 11 May.[49]

At the same time, Japan's progress in China was still not much, although the nationalist and communist Chinese began fighting each other again.[50] Japan was planning to take over European colonies in Asia while they were weak, and the Soviet Union could feel a danger from Germany, so a non-aggression pact (which was an agreement that both countries would not attack each other) between the two was signed in April 1941.[51] However, Germany kept preparing an attack on the Soviet Union, moving its soldiers close to the Soviet border.[52]

The war becomes global

On June 22, 1941, the European Axis countries attacked the Soviet Union. During the summer, the Axis quickly captured Ukraine and the Baltic regions, which caused huge damage to the Soviets. Britain and the Soviet Union formed a military alliance between them in July.[53] Although there was great progress in the last two months, when winter arrived, the tired German army was forced to delay its attack just outside Moscow.[54] It showed that the Axis had failed its main targets, while the Soviet army was still not weakened. This marked the end of the blitzkrieg stage of the war.[55]

By December, the Red Army facing the Axis army had received more soldiers from the east. It began a counter-attack that pushed the German army to the west.[56] The Axis lost a lot of soldiers but it still saved most of the land it received before.[57]

By November 1941, the Commonwealth counter-attacked the Axis in North Africa and got all the land it lost before.[58] However, the Axis pushed the Allies back again until stopped at El Alamein.[59]

In Asia, German successes encouraged Japan to call for oil supplies from the Dutch East Indies.[60] Many Western countries reacted to the occupation of French Indochina by banning oil trading with Japan.[61] Japan planned to take over European colonies in Asia to create a great defensive area in the Pacific so that it could get more resources.[62] But before any future invasion, it first had to destroy the American Pacific Fleet in the Pacific Ocean.[63] On December 7, 1941, it attacked Pearl Harbor as well as many harbors in several South East Asian countries.[64] This event led the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Western Allies and China to declare war on Japan, while the Soviet Union remained neutral.[65] Most of the Axis nations reacted by declaring war on the United States.

By April 1942, many South East Asian countries: Burma, Malaya, the Dutch East Indies and Singapore, had almost fallen to the Japanese.[66] In May 1942, the Philippines fell. The Japanese navy had many quick victories. But in June 1942, Japan was defeated at Midway. Japan could not take more land after this because a large part of its navy was destroyed during the battle.

Allies are advancing

Japan then began its plan to take over Papua New Guinea again,[67] while the United States planned to attack the Solomon Islands. The fight on Guadalcanal began in September 1942 and involved a lot of troops and ships from both sides. It ended with the Japanese defeat in early 1943.[68]

On the Eastern Front, the Axis defeated Soviet attacks during summer and began its own main offensive to southern Russia along Don and Volga Rivers in June 1942, trying to take over oil fields in Caucasus, critical to the Axis for fueling their war effort, and a great steppe. Stalingrad was in the path of the Axis army, and the Soviets decided to defend the city. By November the Germans had nearly taken Stalingrad, however the Soviets were able to surround the Germans during winter[69] After heavy losses, the German army was forced to surrender the city in February 1943.[70] Even though the front was pushed back further than it was before the summer attacks, the German army still had become dangerous to an area around Kursk.[71] Hitler devoted almost two-thirds of his armies to The Battle of Stalingrad. The Battle of Stalingrad was the largest and deadliest battle in this world's time.

In August 1942, because of the Allied defense at El Alamein, the Axis army failed to take the town. A new Allied offensive, drove the Axis west across Libya a few months later,[72] just after the Anglo-American invasion of French North Africa forced it to join the Allies.[73] This led to Axis defeat in the North African Campaign May 1943.[74]

In the Soviet Union, on July 4, 1943, Germany started an attack around Kursk. Many German soldiers were lost because of the Soviets' well-created defenses.[75][76] Hitler canceled the attack before any clear outcome.[77] The Soviets then started their own counter-attack, which was one of the turning points of the war. After this, the Soviets became the attacking force on the Eastern Front, instead of the Germans.[78][79]

On July 9, 1943, affected by the earlier Soviet victories, the Western Allies landed on Sicily. This resulted in the arrest of Mussolini in the same month.[80] In September 1943, the Allies invaded mainland Italy, following the Italian armistice with the Allies.[81] Germany then took control of Italy and disarmed its army,[82] and built up many defensive lines to slow the Allied invasion down.[83] German special forces then rescued Mussolini, who then soon created the German-occupied client state, Italian Social Republic.[84]

Late in 1943 Japan conquered some islands in India and began an invasion of the Indian mainland. The Army of India and other forces expelled them in early 1944.

In early 1944, the Soviet army drove off the German army from Leningrad,[85] ending the longest and deadliest siege in history. After that, the Soviets began a big counter-attack. By May, the Soviets had retaken Crimea. With the attacks in Italy from September 1943, the Allies succeeded in capturing Rome on June 4, 1944, and made the German forces fall back.[86]

The end in Europe

On D-Day, June 6, 1944, the Allies began the invasion of Normandy, France. The code name for the invasion was Operation Overlord. The invasion was successful, and led to the defeat of the German forces in France. Paris was freed on August 1944 and the Allies continued eastward while the German front collapsed. Operation Market-Garden was the combined aerial invasion of the Netherlands launched on September 17, 1944. The purpose of the invasion was to seize a series of bridges that included a bridge in Arnhem, which spanned the Rhine river. Market was the name for the airborne invasion. The ground invasion, named Garden, reached the Rhine river, but could not take the Arnhem bridge. .

On June 22, the Soviet offensive on the Eastern Front, codenamed Operation Bagration, almost destroyed the German Army Group Centre.[87] Soon after, the Germans were forced to retreat and defend Ukraine and Poland. Arriving Soviet troops caused uprisings against the German government in Eastern European countries, but these failed to succeed unless helped by the Soviets.[88] Another Soviet offensive forced Romania and Bulgaria to join the Allies.[89] Communist Serbs partisans under Josip Broz Tito retook Belgrade with some help from Bulgaria and the Soviet Union. By early 1945, the Soviets attacked many German-occupied countries: Greece, Albania, Yugoslavia and Hungary. Finland switched to the side of the Soviets and Allies.

On December 16, 1944, the Germans tried one last time to take the Western Front by attacking the Allies in Ardennes, Belgium, in a battle is known as the Battle of the Bulge. This was the last major German attack of the war, and the Germans were not successful in their attack.[90]

By March 1945, the Soviet army moved quickly from Vistula River in Poland to East Prussia and Vienna, while the Western Allies crossed the Rhine. In Italy, the Allies pushed forward, while the Soviets attacked Berlin. The allied western forces would eventually meet up with the Soviets at the Elbe river on April 25, 1945.

Hitler committed suicide on April 30, 1945, two days after Mussolini's death.[91] In his will, he appointed his navy commander, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, to be the President of Germany.[92] Dönitz surrendered to the Allies, and opposed Hitler's will to have Germany continue fighting.

German forces in Italy surrendered on April 29, 1945. Germany surrendered to the Western Allies on May 7, 1945, known as V-E Day, and was forced to surrender to the Soviets on May 8, 1945. The final battle in Europe was ended in Italy on May 11, 1945.[93]

The end in the Pacific

In the Pacific, American forces arrived in the Philippines on June 1944. And by April 1945, American and Philippine forces had cleared much of the Japanese forces, but the fighting continued in some parts of the Philippines until the end of the war.[94] British and Chinese forces advanced in Northern Burma and captured Rangoon by May 3, 1945.[95] American forces then took Iwo Jima by March and Okinawa by June 1945.[96] Many Japanese cities were destroyed by Allied bombings, and Japanese imports were cut off by American submarines.

The Allies wanted Japan to surrender with no terms, but Japan refused. This resulted in the United States dropping two atomic bombs over Hiroshima (August 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (August 9, 1945). On August 8, 1945, the Soviets invaded Manchuria, quickly defeating the primary Imperial Japanese Army there.[97] On August 15, 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allies. The surrender documents were formally signed on board the USS Missouri on September 2, 1945, ending the war.[98]

At the end

The Allies managed to occupy Austria and Germany. Germany was divided in half. The Soviet Union controlled the Eastern part, and the Western Allies controlled the Western part. The Allies began denazification, removing Nazi ideas from public life in Germany,[99] and most high-ranking Nazis were captured and brought to a special court. Germany lost a quarter of the land it had in 1937, with the land given to Poland and the Soviet Union. The Soviets also took some parts of Poland[100][101][102] and Finland,[103] as well as three Baltic countries.[104][105]

The United Nations was formed on October 24, 1945,[106] to keep peace between countries in the world.[107] However, the relationship between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union had worsened during the war[108] and, soon after the war, each power quickly built up their power over controlled area. In Western Europe and West Germany, it was the United States, while in East Germany and Eastern Europe, it was the Soviet Union, in which many countries were turned into Communist states. The Cold War started after the formation of the American-led NATO and the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact.[109]

In Asia, Japan was put under American occupation. In 1948, Korea was divided into North and South Korea, each claiming to be the legal representative of the Koreans, which led to the Korean War in 1950.[110] Civil war in China continued from 1946 and resulted in the KMT retreating to Taiwan in 1949.[111] The communists won the mainland. In the Middle East, the Arab disagreement on the United Nations plan to create Israel marked the beginning of conflicts between the Arabs and Israel.

After the war, decolonization took place in many European colonies.[112] Bad economies and people wanting to rule themselves were the main reasons for that. In most cases, it happened peacefully, except in some countries, such as Indochina and Algeria.[113] In many regions, European withdrawal caused divisions among the people who had different ethnic groups or religions.[114]

Economic recovery was different in many parts of the world. In general, it was quite positive. The United States became richer than any other country and, by 1950, it had taken over the world's economy.[115][116] It also ordered the Marshall Plan (1948–1951) to help European countries. German,[117] Italian,[118][119] and French economies recovered.[120] However, the British economy was badly harmed[121] and continued to worsen for more than ten years.[122] The Soviet economy grew very fast after the war was over.[123] This also happened with the Japanese economy, which became one of the largest economies in the 1980s.[124] China returned to the same production level as before the war by 1952.[125]

Effect

Death and war crimes

There is no exact total number of deaths, because many were unrecorded. Many studies said that more than 60 million people died in the war, mostly civilians. The Soviet Union lost around 27 million people,[126] almost half of the recorded number.[127] This means that 25% of the Soviets were killed or wounded in the war.[128] About 85% of the total deaths were on the Allies side, and the other 15% were on the Axis. Mostly, people died because they were sick, hungry to death, bombed, or killed because of their ethnicity.

The Nazis killed many groups of people they selected, known as The Holocaust. They exterminated Jews, and killed the Roma, Poles, Russians, homosexuals and other groups.[129] Around 11[130] to 17 million[131] civilians died. Around 7.5 million people were killed in China by the Japanese.[132] The most well-known Japanese crime is the Nanking Massacre, in which hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians were raped and murdered. There were reports that the Germans and Japanese tested biological weapons against civilians[133] and prisoners of war.[134]

Although many of the Axis's crimes were brought to the first international court,[135] crimes caused by the Allies were not.

Concentration camps and slave work

Other than the Holocaust, about 12 million people, mostly Eastern Europeans, were forced to work for the German economy.[136] German concentration camps and Soviet gulags caused a lot of death. Both treated prisoners of war badly. This was even the case for Soviet soldiers who survived and returned home.

Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, many of which were used as labour camps, also caused a lot of deaths. The death rate of Western prisoners was 27.1%,[137] seven times that of prisoners under Germans and Italians.[138] More than 10 million Chinese civilians were made slaves and had to work in mines and war factories.[139] Between 4 and 10 million people were forced to work in Java.[140]

Between 1942 and 1945, Roosevelt signed an order which made Japanese Americans go to internment camps. Some Germans and Italians were included too.

The Allies agreed that the Soviet Union could use prisoners of war and civilians for forced labor.[141] Hungarians were forced to work for the Soviet Union until 1955.[142]

Home fronts and production

Before the war, in Europe, the Allies had a larger population and economy than the Axis. If colonies are included, the GDP of the Allies then would be two times of that of the Axis.[143] While in Asia, China had only 38% higher GDP than the Japanese if their colonies are counted.[143]

The Allies' economy and population compared with the Axis' lessened with the early Axis victories. However, this was no longer the case after the United States and Soviet Union joined the Allies in 1941. The Allies were able to have a higher production level compared with the Axis because the Allies had more natural resources. Also, Germany and Japan did not plan for a long war and had no ability to do so.[144][145] Both tried to improve their economies by using slave laborers.[146]

Women

As men went off to fight, women took over many of the jobs they left behind. At factories, women were employed to make bombs, guns, aircraft, and other equipment. In Britain, thousands of women were sent to work on farms as part of the Land Army. Others formed the Women's Royal Naval Service to help with building and repairing ships. Even Princess Elizabeth, who later became Queen Elizabeth II, worked as a mechanic to aid the war effort. By 1945 some weapons were made almost entirely by women.

In the beginning, women were rarely used in the labour forces in Germany and Japan.[147][148] However, Allied bombings[149][150] and Germany's change to a war economy made women take a greater part.[151]

In Britain, women also worked in gathering intelligence, at Bletchley Park and other places. The mass evacuation of children also had a major impact on the lives of mothers during the war years.

Occupation

Germany had two different ideas of how it would occupy countries. In Western, Northern, and Central Europe, Germany set economic policies which would make it rich. During the war, these policies brought as much as 40% of total German income.[152] In the East, the war with the Soviet Union meant Germany could not use the land to gain resources. The Nazis used their racial policy and murdered a lot of people they thought non-human. The Resistance, the group of people who fought Germany secretly, could not harm the Nazis much until 1943.[153][154]

In Asia, Japan claimed to free colonised Asian countries from European colonial powers.[155] Although they were welcomed at first in many territories, their cruel actions turned the opinions against them within a short time.[156] During the occupation, Japan used 4 million barrels of oil left behind by the Allies at the war's end. By 1943, it was able to produce up to 50 million barrels of oil in the Dutch East Indies. This was 76% of its 1940 rate.[156]

Developments in technology

The war brought new methods for future wars. The air forces improved greatly in fields such as air transport,[157] strategic bombing (to use bombs to destroy industry and morale),[158] as well as radar, and weapons for destroying aircraft. Jet aircraft were developed and would be used in worldwide air forces.[159]

At sea, the war focused on using aircraft carriers and submarines. Aircraft carriers soon replaced battleships.[160][161][162] The important reason was they were cheaper.[163] Submarines, a deadly weapon since World War I,[164] also played an important part in the war. The British improved weapons for destroying submarines, such as sonar, while the Germans improved submarine tactics.[165]

The style of war on the land changed from World War I to be more moveable. Tanks, which were used to support infantry, changed to a primary weapon.[166] The tank was improved in speed, armour and firepower during the war. At the start of the war, most commanders thought that using better tanks was the best way to fight enemy tanks.[167] However, early tanks could harm armour just a little. The German idea to avoid letting tanks fight one another meant tanks facing tanks rarely happened. This was a successful tactic used in Poland and France.[166] Ways to destroy tanks also improved. Even though vehicles became more used in the war, infantry remained the main part of the army,[168] and most equipped like in World War I.[169]

Submachine guns became widely used. They were especially used in cities and jungles.[169] The assault rifle, a German development combining features of the rifle and submachine gun, became the main weapon for most armies after the war.[170]

Other developments included better encryption for secret messages, such as the German Enigma. Another feature of military intelligence was the use of deception, especially by the Allies. Others include the first programmable computers, modern missiles and rockets, and the atomic bombs.

Countries suffering the most warship losses in World War II

| Country | Warships that were sunk |

|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 213 |

| Japan | 198 |

| United States | 105 |

| Italy | 97 |

| Germany | 60 |

| USSR | 37 |

| Canada | 17 |

| France | 11 |

| Australia | 9 |

| Norway | 2 |

Countries suffering the most military losses in World War II

The actual numbers killed in World War II have been the subject heretofore. Most authorities now agree that of the 30 million Soviets who bore arms, there were 13.6 million military deaths.

| Country | Killed |

|---|---|

| USSR | 13,600,000* |

| Germany | 3,300,000 |

| China | 1,324,516 |

| Japan | 1,140,429 |

| British Empire** | 357,116 |

| Romania | 350,000 |

| Poland | 320,000 |

| Yugoslavia | 305,000 |

| United States | 292,131 |

| Italy | 279,800 |

*total, of which 7,800,000 battlefield deaths

**Inc. Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand, etc.

Countries suffering the most civilian losses in World War II

Deaths among civilians during this war - many resulting from famine and internal purges, such as those in China and the USSR - were colossal, but they were less well documented than those among fighting forces. Although the figures are the best available from authoritative sources, and present a broad picture of the scale of civilian losses, the precise numbers will never be known.

| Country | Killed |

|---|---|

| China | 8,000,000 |

| USSR | 6,500,000 |

| Poland | 5,300,000 |

| Germany | 2,350,000 |

| Yugoslavia | 1,500,000 |

| France | 470,000 |

| Greece | 415,000 |

| Japan | 393,400 |

| Romania | 340,000 |

| Hungary | 300,000 |

The Axis Powers

Germany, Italy, Japan, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria

The Allied Powers

U.S., Britain, France, USSR, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Denmark, Greece, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, South Africa, Yugoslavia

Related pages

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lua error in Module:Commons_link at line 62: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).. |

Notes

- ↑ While various other dates have been proposed as the date on which World War II began or ended, this is the time span that is most frequently cited.

References

- ↑ Keegan, John (1989), The Second World War, Glenfield, Auckland 10, New Zealand: Hutchinson

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ source list and detailed death tolls for the twentieth century hemoclysm.

- ↑ Beevor, Antony (2012). The Second World War. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-297-84497-6.

- ↑ "Holocaust Encyclopedia". Military Operations in North Africa. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 29 January 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ↑ (in en) Rhine River | river, Europe. https://www.britannica.com/place/Rhine-River. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ↑ Gerhard Weinberg 1970. The foreign policy of Hitler's Germany diplomatic revolution in Europe 1933-36, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p 346.

- ↑ Robert Melvin Spector. World without civilization: mass murder and the Holocaust, history, and analysis, pg. 257

- ↑ Ian Dear; Michael Richard Daniell Foot (2001). The Oxford companion to World War II. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 674. ISBN 978-0-19-860446-4.

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard L. (1995). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-521-55879-2.

- ↑ Hakim, Joy (1995). War, Peace and All That Jazz. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-509514-2.

- ↑ "Reparations and post-war Germany". Alpha History. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ↑ Kantowicz, Edward R. (1999). The Rage of Nations. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8028-4455-2.

- ↑ Shaw, Anthony (2000). World War II day by day. MBI Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7603-0939-1. p. 35

- ↑ Preston, Peter (1998). Pacific Asia in the Global System: An Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-631-20238-7.

- ↑ Ralph Steadman, Winston Smith 2004. All riot on the Western Front. Last gasp, p. 28. ISBN 978-0-86719-616-0

- ↑ Busky, Donald F. (2002). Communism in History and Theory: Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-275-97733-7.

- ↑ Fairbank, John King; Twitchett, Denis Crispin; Loewe, Michael; Chaffee, John W.; Smith, Paul J.; Franke, Herbert; Mote, Frederick W.; Feuerwerker, Albert; Liu, Kwang-Ching; Peterson, Willard J.; MacFarquhar, Roderick (1978). The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge University Press. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-521-24338-4.

- ↑ Bullock, A. (1962). Hitler: A study in tyranny. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013564-0. p. 162.

- ↑ Brody, J. Kenneth (1999). The Avoidable War: Pierre Laval & the politics of reality, 1935-1936. Transaction Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7658-0622-2.

- ↑ Collier, Martin; Pedley, Philip (2000). Germany 1919–45. Heinemann. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-435-32721-7.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian (2001). Hitler, 1936-45: Nemesis. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-0-393-32252-1.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian (2001). Hitler, 1936-45: Nemesis. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-393-32252-1.

- ↑ Davies, Norman (2008). No Simple Victory: World War II in Europe, 1939-1945. Penguin. pp. 143–4. ISBN 978-0-14-311409-3.

- ↑ Andrew J. Crozier. The Causes of the Second World War, pg. 151

- ↑ Shore, Zachary 2005. What Hitler knew: the battle for information in Nazi foreign policy. Oxford University Press, p. 108.

- ↑ Ian Dear; Michael Richard Daniell Foot (2001). The Oxford companion to World War II. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 608. ISBN 978-0-19-860446-4.

- ↑ May, Ernest R (2000) (Google books). Strange Victory: Hitler's Conquest of France. I.B.Tauris. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-85043-329-3. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- ↑ Zaloga Steven J,, Howard Gearad (2002) (Google books). Poland 1939: The Birth of Blitzkrieg. Osprey Publishing. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-84176-408-5. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- ↑ Smith, David J. (2002) (Google books). The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Routledge. 1st edition. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-415-28580-3. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- ↑ Spring, D. W (April 1986). The Soviet Decision for War against Finland, 30 November 1939. Europe-Asia Studies 38 (2): 207–226.

- ↑ Hanhimäki, Jussi M (1997) (Google books). Containing Coexistence: America, Russia, and the "Finnish Solution". Kent State University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-87338-558-9. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- ↑ Murray, Williamson; Millett, Allan Reed (2001). A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00680-5. p.55-6

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard L. (1995). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge University Press. p. 95, 121. ISBN 978-0-521-55879-2.

- ↑ Murray, Williamson; Millett, Allan Reed (2001), A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-00680-5. p.57-63

- ↑ Reynolds, David (27 April 2006). From World War to Cold War: Churchill, Roosevelt, and the International History of the 1940s (Google books). Oxford University Press, USA. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-19-928411-5. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ↑ Crawford, Keith; Foster, Stuart J (2007) (Google books). War, nation, memory: international perspectives on World War II in school history textbooks. Information Age Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-59311-852-5. . Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- ↑ Klaus, Autbert (2001). Germany and the Second World War Volume 2: Germany's Initial Conquests in Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 311. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- ↑ Bilinsky, Yaroslav (1999) (Google books). Endgame in NATO's Enlargement: The Baltic States and Ukraine. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-275-96363-7. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- ↑ H. W. Koch. Hitler's 'Programme' and the Genesis of Operation 'Barbarossa'. The Historical Journal, Vol. 26, No. 4 (Dec. 1983), pp. 891-920

- ↑ Roberts, Geoffrey (2006). Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953. Yale University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-300-11204-7.

- ↑ Roberts, Geoffrey (2006). Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953. Yale University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-300-11204-7.

- ↑ Kelly, Nigel; Rees, Rosemary; Shuter, Jane (1998). The Twentieth Century World. Heinemann. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-435-30983-1.

- ↑ Goldstein, Margaret J (2004). World War II. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8225-0139-8.

- ↑ Murray, Williamson; Millett, Allan Reed (2001). A war to be won: fighting the Second World War. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00680-5. p. 233-45

- ↑ Clogg, Richard (2002). A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-521-80872-9.

- ↑ Murray, Williamson; Millett, Allan Reed (2001), A war to be won: fighting the Second World War, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-00680-5. p. 263-267.

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard L. (1995). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-521-55879-2.

- ↑ The London Blitz, 1940. Eyewitness to History. 2001. Retrieved March 11, 2008.

- ↑ Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (1994). China: A New History. Harvard University Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-674-11673-3.

- ↑ Garver, John W. (1988). Chinese-Soviet Relations, 1937-1945: The Diplomacy of Chinese Nationalism. Oxford University Press on Demand. p. 114. ISBN 0-19-505432-6.

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard L. (1995). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-521-55879-2.

- ↑ Pravda, Alex; Duncan, Peter J. S (1990). Soviet-British Relations Since the 1970s. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-521-37494-1.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt (Dr. Generalmajor i.G.) (1992). Moscow: The Turning Point?: The Failure of Hitler's Strategy in the Winter of 1941-42. Berg Publishing Limited. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-85496-695-0.

- ↑ Milward, A.S. (1964). The End of the Blitzkrieg. The Economic History Review. 16 (3): 499–518.

- ↑ Welch, David (1999). Modern European History, 1871-2000: A Documentary Reader. Psychology Press. p. 102. ISBN 0-415-21582-X.

- ↑ Glantz, David M. (2001), Soviet‐German War 1941–45 Myths and Realities: A Survey Essay. p.31

- ↑ Gannon, James (2002). Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth Century. Brassey's. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-57488-473-9.

- ↑ Rich, Norman (1992). Hitler's War Aims: Ideology, the Nazi State, and the Course of Expansion. Norton. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-393-00802-9.

- ↑ AFLMA Year in Review, p. 32.

- ↑ Northrup, Cynthia Clark (2003). The American Economy: Essays and primary source documents. ABC-CLIO. p. 214. ISBN 1-57607-866-3.

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard L (2005). A World At Arms. Cambridge University Press. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-521-61826-7.

- ↑ Morgan, Patrick M (1983). Strategic Military Surprise: Incentives and Opportunities. Transaction Publishers. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-87855-912-1.

- ↑ Wohlstetter, Roberta (1962). Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision. Stanford University Press. pp. 341–43. ISBN 978-0-8047-0597-4.

- ↑ Dunn, Dennis J (1998). Caught Between Roosevelt & Stalin: America's Ambassadors to Moscow. The University Press of Kentucky. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-8131-2023-2.

- ↑ Klam, Julie (2002). The Rise of Japan and Pearl Harbor. Black Rabbit Books. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-58340-188-0.

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard L. (1995). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge University Press. p. 339. ISBN 978-0-521-55879-2.

- ↑ Hane, Mikiso (2001). Modern Japan: A Historical Survey. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-8133-3756-2.

- ↑ Badsey, Stephen (2000). The Hutchinson Atlas of World War Two Battle Plans: Before and After. Taylor & Francis. p. 235-36. ISBN 978-1-57958-265-4.

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin (2004). The Second World War: A Complete History. Elsevier. p. 397-400. ISBN 978-0-8050-7623-3.

- ↑ Shukman, Harold (2002). Stalin's Generals. Author House. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-84212-513-7.

- ↑ Thomas, Nigel (1998). The German Army 1939–45 (2): North Africa & Balkans. Osprey Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-85532-640-8.

- ↑ Ross, Steven T. (1997). American War Plans, 1941-1945: The Test of Battle. Psychology Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-7146-4634-2.

- ↑ Collier, Paul (2003). The Second World War (4): The Mediterranean 1940–1945. Osprey Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-84176-539-6.

- ↑ Glantz. (1986), "Soviet Defensive Tactics at Kursk, July 1943", CSI Report No. 11., OCLC 278029256. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ↑ Glantz, David M. (1989). Soviet Military Deception in the Second World War. Psychology Press. p. 149–59. ISBN 0-7146-3347-X.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian (2001). Hitler, 1936-45: Nemesis. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 592. ISBN 978-0-393-32252-1.

- ↑ O'Reilly, Charles T. (2001). Forgotten Battles: Italy's War of Liberation, 1943-1945. Lexington Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-7391-0195-7.

- ↑ Healy, Mark (1992). Kursk 1943: The tide turns in the East. Osprey Publishing. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-85532-211-0.

- ↑ O'Reilly, Charles T. (2001). Forgotten Battles: Italy's War of Liberation, 1943-1945. Lexington Books. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7391-0195-7.

- ↑ McGowen, Tom (2002). Assault from the Sea: Amphibious Invasions in the Twentieth Century. Lerner Publications. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7613-1811-8.

- ↑ Lamb, Richard (1996). War In Italy, 1943-1945: A Brutal Story. Da Capo Press. p. 154-55. ISBN 978-0-306-80688-9.

- ↑ Hart, Stephen; Hart, Russell; Hughes, Matthew (2000). The German Soldier in World War II. Zenith Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-7603-0846-2.

- ↑ Blinkhorn, Martin (1994). Mussolini and Fascist Italy. Psychology Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-415-10231-6.

- ↑ Glantz, David M. (2001). The Siege of Leningrad, 1941-1944: 900 Days of Terror. Zenith Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-7603-0941-4.

- ↑ Havighurst, Alfred F. (1985). Britain in Transition: The Twentieth Century. University of Chicago Press. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-226-31971-1.

- ↑ Zaloga, Steven J. (1996). Bagration 1944: The Destruction of Army Group Centre. Osprey Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-85532-478-7.

- ↑ Berend, Ivan (1996). Central and Eastern Europe, 1944-1993: Detour from the Periphery to the Periphery. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-521-55066-6.

- ↑ Armistice Negotiations and Soviet Occupation. US Library of Congress. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ↑ Parker, Danny (2004). Battle of the Bulge: Hitler's Ardennes Offensive, 1944-1945. Da Capo Press. pp. xiii–xiv, 6–8, 68–70 & 329–330. ISBN 978-0-306-81391-7.

- ↑ O'Reilly, Charles T. (2001). Forgotten Battles: Italy's War of Liberation, 1943-1945. Lexington Books. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-7391-0195-7.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian (2001). Hitler, 1936-45: Nemesis. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 823. ISBN 978-0-393-32252-1.

- ↑ Glantz, David M.; House, Jonathan M. (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7006-0899-7.

- ↑ Chant, Christopher (1986). The Encyclopedia of Codenames of World War II. Routledge. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-7102-0718-0.

- ↑ Drea, Edward J. (2003). In the Service of the Emperor: Essays on the Imperial Japanese Army. University of Nebraska Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8032-6638-4.

- ↑ Jowett, Philip (2002). The Japanese Army 1931–45 (1): 1931–42. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-353-8.

- ↑ Glantz, David M (2005), "August Storm: The Soviet Strategic Offensive in Manchuria". Archived from the original on 2 March 2008., Leavenworth Papers (Combined Arms Research Library), OCLC 78918907. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ↑ Donnelly, Mark (1999). Britain in the Second World War. Psychology Press. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-415-17425-1.

- ↑ World War Two and Germany, 1939-1945. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zwrfj6f/revision/5. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ Roberts, Geoffrey (2006). Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953. Yale University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-300-11204-7.

- ↑ Roberts, Geoffrey (2006). Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953. Yale University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-300-11204-7.

- ↑ Shirer, William L. (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. Simon and Schuster. p. 794. ISBN 978-0-671-72868-7.

- ↑ Kennedy-Pipe, Caroline (1995). Stalin's Cold War. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4201-0.

- ↑ Wettig, Gerhard (2008). Stalin and the Cold War in Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-7425-5542-6.

- ↑ Senn, Alfred Erich (2007). Lithuania 1940: revolution from above. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-2225-6.

- ↑ History of the UN. United Nations. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ↑ Yoder, Amos (1997). The Evolution of the United Nations System. Taylor & Francis. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-56032-546-8.

- ↑ Kantowicz, Edward R (2000). Coming Apart, Coming Together. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8028-4456-9.

- ↑ Leffler, Melvyn P.; Painter, David S (1994). Origins of the Cold War: An International History. Routledge. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-415-34109-7.

- ↑ Connor, Mary E. (2009). "History". In Connor, Mary E. (ed.). The Koreas. Asia in Focus. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 43–45. ISBN 978-1-59884-160-2.

- ↑ Lynch, Michael (2010). The Chinese Civil War 1945–49. Botley: Osprey Publishing. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-1-84176-671-3.

- ↑ Betts, Raymond F. (2004). Decolonization. Routledge. pp. 21–24. ISBN 978-0-415-31820-4.

- ↑ Conteh-Morgan, Earl (2004). Collective Political Violence: An Introduction to the Theories and Cases of Violent Conflicts. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-415-94744-2.

- ↑ Vess, Deborah (2001). "Chapter 7, The impact on colonialism: the Middle East, Africa, and Asia in crisis following World War II". AP World History: The Best Preparation for the AP World History Exam (Google books). Research & Education Association. p. 564. ISBN 978-0-7386-0128-1. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- ↑ Harrison, Mark (1998). "The economics of World WarII: an overview". In Harrison, Mark (ed.). The Economics of World War II: Six great powers in international comparison. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-0-521-62046-8.

- ↑ Dear, I.C.B and Foot, M.R.D. (editors) (2005). "World trade and world economy". The Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 1006. ISBN 978-0-19-280670-3.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Rudiger Dornbusch (1993). Postwar Economic Reconstruction and Lessons for the East Today. Wilhelm Nölling, Richard Layard, P. Richard G. Layard. MIT Press. p. 29-30, 32. ISBN 978-0-262-04136-2.

- ↑ Bull, Martin J.; Newell, James (2005). Italian Politics: Adjustment Under Duress. Polity. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7456-1299-7.

- ↑ Bull, Martin J.; Newell, James (2005). Italian Politics: Adjustment Under Duress. Polity. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7456-1299-7.

- ↑ Harrop, Martin (1992). Power and Policy in Liberal Democracies. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-521-34579-8.

- ↑ Dornbusch, Rüdiger; Nölling, Wilhelm; Layard, P. Richard G (1993). Postwar Economic Reconstruction and Lessons for the East Today. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-262-04136-2.

- ↑ Emadi-Coffin, Barbara (2002). Rethinking International Organization: Deregulation and Global Governance. Routledge. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-415-19540-9.

- ↑ Smith, Alan (1993). Russia And the World Economy: Problems of Integration. Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-415-08924-1.

- ↑ Harrop, Martin (1992). Power and Policy in Liberal Democracies. Cambridge University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-521-34579-8.

- ↑ Genzberger, Christine (1994). China Business: The Portable Encyclopedia for Doing Business with China. Petaluma, California: World Trade Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-9631864-3-0.

- ↑ "Rulers and victims: the Russians in the Soviet Union". Geoffrey A. Hosking (2006). Harvard University Press. p.242. ISBN 978-0-674-02178-5

- ↑ "Leaders mourn Soviet wartime dead". BBC News. May 9, 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4530565.stm. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- ↑ "The World's Wasted Wealth 2: Save Our Wealth, Save Our Environment". J. W. Smith (1994). p.204. ISBN 978-0-9624423-2-2

- ↑ Todd, Allan (2001). The Modern World. Oxford University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-19-913425-0.

- ↑ Florida Center for Instructional Technology (2005). "Victims". A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust. University of South Florida. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ↑ Niewyk, Donald L. and Nicosia, Francis R. The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust, Columbia University Press, 2000, pp. 45-52.

- ↑ Winter, J. M (2002). "Demography of the War". In Dear, I. C. B.; Foot, M. R. D (eds.). Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford University Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-19-860446-4.

- ↑ Sabella, Robert; Li, Fei Fei; Liu, David (2002). Nanking 1937: Memory and Healing. M.E. Sharpe. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-7656-0816-1.

- ↑ "Japan tested chemical weapons on Aussie POW: new evidence". The Japan Times Online. 27 July 2004. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ↑ Aksar, Yusuf (2004). Implementing International Humanitarian Law: From the Ad Hoc Tribunals to a Permanent International Criminal Court. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-7146-8470-3.

- ↑ Marek, Michael (27 October 2005). "Final Compensation Pending for Former Nazi Forced Laborers". dw-world.de. Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 19 January 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ↑ "Japanese Atrocities in the Philippines". American Experience: the Bataan Rescue. PBS Online. Archived from the original on 19 January 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ Tanaka, Yuki (1996). Hidden Horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II. Westview Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-8133-2718-1.

- ↑ Ju, Zhifen (June 2002). "Japan's atrocities of conscripting and abusing north China draftees after the outbreak of the Pacific war". Joint Study of the Sino-Japanese War:Minutes of the June 2002 Conference. Harvard University Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ↑ "Indonesia: World War II and the Struggle For Independence, 1942–50; The Japanese Occupation, 1942–45". Library of Congress. 1992. Retrieved 9 February 2007.

- ↑ Eugene Davidson "The death and life of Germany: an account of the American occupation". p.121

- ↑ Stark, Tamás. ""Malenki Robot" – Hungarian Forced Labourers in the Soviet Union (1944–1955)" (PDF). Minorities Research. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- ↑ 143.0 143.1 Harrison, Mark (2000). The Economics of World War II: Six Great Powers in International Comparison. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-521-78503-7.

- ↑ Cox, Sebastian (1998). The Strategic Air War Against Germany, 1939–1945. Frank Cass Publishers. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-7146-4722-7.

- ↑ Unidas, Naciones (2005). World Economic And Social Survey 2004: International Migration. United Nations Pubns. p. 23. ISBN 978-92-1-109147-2.

- ↑ Hughes, Matthew; Mann, Chris (2000). Inside Hitler's Germany: Life Under the Third Reich. Potomac Books Inc. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-57488-281-0.

- ↑ Bernstein, Gail Lee (1991). Recreating Japanese Women, 1600–1945. University of California Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-520-07017-2.

- ↑ Hughes, Matthew; Mann, Chris (2000). Inside Hitler's Germany: Life Under the Third Reich. Potomac Books Inc. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-57488-281-0.

- ↑ Griffith, Charles (1999). The Quest: Haywood Hansell and American Strategic Bombing in World War II. DIANE Publishing. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-58566-069-8.

- ↑ Overy, R.J (1995). War and Economy in the Third Reich. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-19-820599-9.

- ↑ Milward, Alan S (1979). War, Economy, and Society, 1939–1945. University of California Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-520-03942-1.

- ↑ Hill, Alexander (2005). The War Behind The Eastern Front: The Soviet Partisan Movement In North-West Russia 1941–1944. Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7146-5711-0.

- ↑ Christofferson, Thomas R; Christofferson, Michael S (2006). France During World War II: From Defeat to Liberation. Fordham University Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-8232-2563-7.

- ↑ Ikeo, Aiko (1997). Economic Development in Twentieth Century East Asia: The International Context. Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-415-14900-6.

- ↑ 156.0 156.1 Boog, Horst; Rahn, Werner; Stumpf, Reinhard; Wegner, Bernd (2001). Militargeschichtliches Forschungsamt Germany and the Second World War—Volume VI: The Global War. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-19-822888-2.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2004). Encyclopedia of World War II: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-57607-999-7.

- ↑ Levine, Alan J. (1992). The Strategic Bombing of Germany, 1940–1945. Greenwood Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-275-94319-6.

- ↑ Sauvain, Philip (2005). Key Themes of the Twentieth Century: Teacher's Guide. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-4051-3218-3.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2004). Encyclopedia of World War II: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-57607-999-7.

- ↑ Chenoweth, H. Avery; Nihart, Brooke (2005). Semper Fi: The Definitive Illustrated History of the U.S. Marines. Main Street. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-4027-3099-3.

- ↑ Hearn, Chester G. (2007). Carriers in Combat: The Air War at Sea. Stackpole Books. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8117-3398-4.

- ↑ Burcher, Roy; Rydill, Louis J. (1995). Concepts in Submarine Design. Cambridge University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-521-55926-3.

- ↑ Burcher, Roy; Rydill, Louis J. (1995). Concepts in Submarine Design. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-521-55926-3.

- ↑ 166.0 166.1 Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2004). Encyclopedia of World War II: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-57607-999-7.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2004). Encyclopedia of World War II: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-57607-999-7.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2004). Encyclopedia of World War II: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 734. ISBN 978-1-57607-999-7.

- ↑ 169.0 169.1 Cowley, Robert; Parker, Geoffrey (2001). The Reader's Companion to Military History. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-618-12742-9.

- ↑ Sprague, Oliver; Griffiths, Hugh (2006). "The AK-47: the worlds favourite killing machine" (PDF). controlarms.org. p. 1. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

Other websites

- World War II Letter Database - Letters from World War Two

- WW2 Database - More Info on from WW2

- World War II - Encyc

- Radio News From 1938 to 1945

- Fun facts about WW2 for children